Chapter 8

Children's Mixed Feelings, Hurting and Comforting

As we have seen in the previous chapter prosocial behavior is exhibited by infants and very young children studied in a wartime nursery context, in laboratory settings, in parental home contexts, and in cross-cultural studies in different community settings around the world, in spite varying caretaking patterns across cultures. An explanation have been offered. The infant is expected to try to attend, or call for attendance, to the actual other in need by virtue of the infant's feeling with his virtual other. That is, an inherent capacity for prosociality is entailed to be exhibited by the infant across different cultures, as long as the actual culture and setting allows for and provides opportunities for such modalities, and irrespective of whether or not there is a cultural demand for prosociality on the part of the socialized child.

If the account of infants' prosociality presented in the previous chapter is tenable, then one should also expect, albeit in different forms that vary with the actual culture and community setting, infant prosociality to be exhibited across different kinds of cultures and actual settings, and not only as a function of the particular caregiving practice and socialization characteristics of the local setting. As will be referred to below, even in the extremely deprived conditions of a group of children rescued from Nazi extermination camps at the end of the second world war, Anna Freud and Dann find indications of mutual care and protection against a hostile worlds

among the tight and self-enclosed group of rescued child victims.

Sigmund Freud identified polar instinctual impulses in the infant's mind. In his work on the Ego and the Id he postulates in the Id the class of destructive instincts (death instincts) as distinct from the class of self-preservation instinct (Eros). For the opposition between them he puts the polarity of hate and love.Sigmund Freud: The Ego and the Id. In: Peter Gay: The Freud Reader. New York: W.W. Norton, 1989, pp.645-649. In order to later avoid becoming the object of the destructive instinct, ego has to "itself to become filled with libido; it thus itself becomes the representative of Eros and thenceforeward desires to live and to be loved."Sigmund Freud, op.cit., p.567.

In a modified manner, based upon her analyses of children, some of whom had suffered neglect by depressive or absent parents during infancy, Melanie Klein also attributes to the infant contrasting impulses, including sadistic ones. Phantastically distorted imagos of objects, some of them as dangerous, are "installed" within the ego of the child already during the first month of life. The baby comes to introject objects 'good' and 'bad' - for good objects when the child obtains it and for bad when it fails him, not only in that they frustrate its desires, but "because the baby projects its own aggression on to these objects that it feels them to be 'bad'.."Melanie Klein: A Contribution to the Psychogenesis of Manic-Depressive States. In: P. Buckley (ed.): Essential Papers on Object RElations. New York University Press, 1986, pp.40-70.

In this chapter I shall specify how the experienced child, by virtue of the dyadic organization of mind, may come to entertain feelings complementary to those of liking, loving, and caring. In some of the communities studied in the cross-cultural study referred to in the previous chapter parents were found to encourage their children to exhibit behavior in dominant and aggressive modes. Such occurrences in infancy are not precluded by the thesis; aggressive interaction can be enacted in a mode of immediate reciprocity. Below I shall indicate how it is that the child, in spite of its innate ground for caring and comforting, also may come to engage in hurting the actual other as a joint consequence of environmental impact and of the way in which the dyadic constitution of the infant's mind allows for the alternating between complementary feelings, and between complementary patterns of behavior in accord with such feelings. Some of the studies referred to in the previous chapter include observations of children expressing threats or hatred, deliberately hurting other children, or showing indifference to others being hurt. Such incidents have been reported by Anna Freud and Berlinghem, by Judy Dunn and Carol Kendrick, by Mary Main and Carol George and by others.

Abuse may be due to a personal history of being abused, as pointed out by Paul Harris (1989). Having experienced abuse already the toddler may come to resort to abusing the other. I shall later indicate how this may entail a conversion of the capacities postulated in (q).

Reports on anti-social and hostile behavior

Consider this episode, reported by Anna Freud and Berlinghem:

(ø6) "38. Freda (21 months) pulled Sam's hair. Sam (21 months) cried but did not defend himself. Jeffrey (2 years, 4 months) crossed the nursery quickly, hit Freda twice, and then comforted Sam..."A. Freud and D. Burlinghem, op.cit., p.577.

The explanation offered in the previous chapter may account for Jeffrey's being able to feel with Sam, while his act of hitting Freda as a third person excluded from their closure falls outside of the domain of implications. Jeffrey is not only comforting an actual other, but is also deliberately hurting another infant. His hitting Freda may, however, be seen as directed to stop her pulling Sam's hair, or as a punishment. If Sam and Jeffrey had established dialogic closure through being actual companions to each other, then Freda's pulling Sam's hair might be seen as directed towards both of them, and again, Jeffrey's action as a reaction against this perturbation. But his act of hitting Freda as a third person cannot be entailed unless there are added statements, for example, about mediate experience and learning to educate the other not to be hurting others. In such a light Jeffrey is punishing Freda as a social act of education, albeit primitive.

If Freda's pulling Sam's hair in a hurtful manner that makes him cry is a deliberate act of hostile intention, carried out in indifference to, or even in pleasure in, the other's hurt feelings, and Freda's behavior cannot be traced back to previous mediating experiences, then this event would count as a disconfirming case with respect to the prediction (8).

Frida is living in a wartime nursery, deprived of family relations. She is 21 month old. I have observed and recorded, however, infants in the middle of their first year who actually hurt each other, albeit it is hard to say whether it is accidental or with intent. For example, Kine (5 1/2 month) and Silje (8 1/2 month), on the lap of Silje's mother, engaged in a kind of interaction which turned into a virtual wrestling match. As pointed out by Rubin, poking curiosity, rather than hostile intent, may be involved in such cases. Yet, if hostile intent was indeed involved in this "wrestling match" perhaps again some mode of protecting the closure might have been involved: Silje may have felt Kine to intrude or perturb the closure of Silje with her mother. In that case, the event concerns the boundary relations between the infant-adult dyad and a perturbing environment, even though the two infants were seen to be clearly interested in each other.

I have observed also how Katharina (15 1/2 month), a year after the incident when she comforted her older sibling, rejected a boy (12 months) crawling towards her sandbox. Even when he starts sobbing, she remains determined to keep him out her territory. When he goes after video-camera bag, which Katharina regards as hers, again she pushes him away. When he starts crying she does not come to his comfort. She does not attack him, but she clearly neglect to do anything about his distress. Now, Katharina lives in a family with four elder siblings, bring in friends all the time. She may have learnt to guard what is hers, and event to use force when necessary to keep intruders from taking what is hers.

Rubin (1980: 15-16) observes his son, Elihu (from eight months onwards) during sessions in his first playgroups. They include four infants - three of them still crawlers. The babies would tend to ignore each other, occasionally looking at each other with what seemed mild interest. However, there were isolated instances in which one baby approached and made physical contact with another, for example:

(ø7) "Vanessa takes Elihu by surprise by crawling to him, screaming and pulling his hair. Elihu looks bewildered. Then he starts to cry and crawls to his mother to be comforted."Z. Rubin, op.cit., p.15.

Rubin considers that such episodes of hair pulling, poking, and pawning by infants (eight or nine months old) did not appear to involve hostile intent. Instead, they seem to reflect the babies' interest in exploring one another.

There are, however, reports about mutual hostility between children, for example between first-borns and baby sibling during the latter's first year. Let us consider one such report.

Hostile behavior and understanding between siblings

In their study of sibling relationships involving loving and hating, understanding and envy, Judy Dunn and Carol Kendrick (1982: 4) point out that to consider the child and the mother as a dyad isolated from the other member of the family can be extremely misleading. They found that as early as in their second year, some of the second-born siblings exhibited a pragmatic understanding not only of how to comfort and console, but also to provoke and annoy the elder child. When six year old, several of the elder children (11 of 19) expressed verbally their dislike of the aggression of the younger siblings (between 42 and 60 months). One girl, for example, complains in this way:

"I don't like her; she is horrible, she is, 'cause uhm hits, disgusting; she shouts at me, hits me, kicks me, hits me."Judy Dunn and Carol Hendrick: Siblings: Love, Envy, & Understanding. London: Grant McIntyre 1982, p.207.

But it appears that occurrences of friendly and hostile behavior between siblings were dependent on how they got on with each from the early beginning. Dunn and Kendrick study 40 firstborn children living in Cambridge, England, with their mothers and fathers. They follow the children for 14 months after the birth of the second child in the family.They also include in their report a follow-up study of the children when they were about six year old. The above quotation is from that follow-up, conducted by Stillwell-Barnes. In cases where the relationships between mother and baby had been intense and playful, they find that six months later both children (the first born and the younger sibling who had been engaged in the playful infant-mother dyad) were particularly hostile to each other.ibid, p.175. A warm and friendly relation to the sibling, on the other hand, appeared to have been encouraged in those children who have a somewhat detached or conflict-laden relationship to their parents (Dunn and Kendrick (1982: 176). They find, for example, that in families where the mothers were depressed or detached due to tiredness during the first three weeks after the second birth, the sibling relationship developed in a more friendly fashion.

Depression or detachment on the part of the parent may have prevented this kind of mutual relations (Cf. Murray's study referred to in chapter 4). The newborn is ready to engage in interaction, inviting actual others to step into the companion space of its virtual other. If adults others are hindered from accepting this invitation, other actual others may come to respond. During the first month of life this involves an invitation to engage in such interplay in a mode of felt immediacy which both siblings will come to experience, and which will provide a foundation for later mediated modes of interaction.

Dunn and Kendrick also report that in families where the first child imitated the baby siblings frequently during the first three weeks, both siblings were particularly friendly to each other also 14 months later. Compared to the younger siblings in the sample, the baby siblings were on the whole significantly more friendly to their elder sibling who were reported to show interest and affection to the baby in the second and third week after birth, than those baby siblings who had not been met with such interest and affection from the first-borns.Dunn and Kendrick, op.cit., p.155-156. The first-born's response, in turn, to events surrounding the birth, turned out to be linked to his response to the baby's behavior towards him as an actual other, to his behavior in relation to the sibling 14 months later, and to his reaction to the mother-sibling dyad involved in play. ibid, p.6.

The first-borns, even those only two years old, showed a sensitivity to the emotional states of the baby sibling and an understanding of the baby's behavior that demonstrated their ability to feel (with) the actual other's perspective. This, again, is to be expected. According to implications of the thesis there is a natural ground, prior to cultural socialization, for the ability to feel with and take the other's perspective. Irrespective of whether it be furthered and hampered through the process of socialization, prosociality is entailed by the collateral to come natural to the infant. Even occurrences in extreme circumstances of intense reciprocal love-hate relationships can be expected, given a previous history of being hated or hurt.

The closure of six children from concentration campsAnna Freud: An Experiment in Group Upbringing, in: The Writings of Anna Freud. Vol. IV 1945-1956. I am grateful to Sophie Freud for this reference.

On October 15, 1945, six German-Jewish orphans arrived in Bulldogs Bank, in a nursery set up by the Foster Parents' Plan for War children. The children, about 3 years old, were victims of the Nazi regime. Their parents, soon after their birth, had been deported to Poland and killed in the gas chambers. As Anna Freud reports, none of them had known any other circumstances of life than those of a group setting. They were ignorant of the meaning of a "family". During their first year of life, after having been handed from one refuge to another, they arrived in the concentration transit camp of Tereszin in Moravia. There they were inmates of the Ward for motherless children until liberation in the spring 1945. They were then sent to a Czeck castle and given special care, before included in a transport to England.

Anna Freud reports how the six children insisted on being together and, at first, resisted any attempts to be separated or treated as individuals. At the same time they behaved aggressively and defensively, creating a shared front against the staff:

"During the first days after arrival they destroyed all the toys and damaged much of the furniture. Toward the staff they behaved either with cold indifference or with active hostility....

They would turn to an adult when they had some immediate need, but treat the same person as non-existent once more when the need was fulfilled. In anger they would hit the adults, bite or spit."op.cit., p. 168.

Within the group there were only verbal aggressiveness. They would quarrel endlessly at mealtimes and on walks, carrying out word-battles in German with an admixture of Czeck words. But the six children, with the exception of one child, did not hurt or attack each other during the first months. There was also an almost complete absence of jealousy, rivalry, and competition among the children. At the time, the adults played no part in their emotional lives. The children were extremely considerate of each other's feelings, helpful, showing concern and care:

"On walks they were concerned for each other's safety in traffic, looked after children who lagged behind, helped each other over ditches, turned aside branches for each other to clear the passage in the woods, and carried each other's coats. In the nursery they picked up each other's toys. After they had learned to play, they assisted each other silently in building and admiring each other's productions. At mealtimes handing food to the neighbor was of greater importance than eating oneself." (Anna Freud, with Sophie Dann, 1951).op.cit, p.174.

The above dramatic observations by Anna Freud and Sophie Dann may be described in terms of the postulated companion space of the children's virtual other. The six orphans are included in each other's companion space in a genuine sense of organizational closure. But during the first months, nobody but the six children were allowed to fill each other's companion space in a mode felt immediacy. The mutually constituted boundary excluded any other than the orphans from entering the companion space. Adult others were at first met with cool indifference or active hostility. They might be seen to threaten and perturb the auto-organizational closure mutually constituted and re-created by the children in concert.

Anna Freud reports that it was evident that they cared greatly for each other and not at all for anybody or anything else. They became upset when they were separated from each other, even for short moments.op.cit., p.169. One of the children did, however, from time to time withdraw from the group. This was Paul, who in his good periods was friendly, attentive, and helpful towards the other, always ready to take up arms against an aggressor. But when he went into his spells of compulsive sucking his thumb or masturbating, the whole environment, including the other members of the group, appeared to lose significance to him.

In terms of the present thesis, during such spells the actual companions were excluded from his companion space. His penis or thumb became a bodily medium for re-creating his own auto-organizational closure in conversation with himself, that is, with his virtual other.

Discussion

The group of orphans from the concentration camps may be seen to illustrate a very strong case of attachment to each other, even protective and loving care.

Even though precarious, the inborn ground for caring may even be brought to the surface against the extremely deprived and cruel background of concentration camps. As we have seen, Anna Freud and Dann report helping, comforting and caring behavior by three-year old children rescued from a concentration camp and deprived of any family life.But perhaps, as suggested by Sophie Freud, and told her by her aunt, considerations of these extreme circumstances prevented one from drawing the full theoretical implications of the reported observations by Anna Freud and her coworkers. Their report published already in 1951, should have been sufficient by itself to have called for a radical revision of traditional theories of development which have attributed to the infant ego-centered, even autistic, closure.

There is infant closure also according to the present thesis. But this is a kind of dialogic closure by virtue of which there is openness to the actual other. It does not preclude self-absorbing states on the pang Freda may, however, be seen as directed to stop her pulling Sam's hair, or as a punishment. If Sam and Jeffrey had established dialogic closure through being actual companions to each other, then Freda's pulling Sam's hair might be seen as directed towards both of them, and again, Jeffrey's action as a reaction against this perturbation. But his act of hitting Freda as a third person cannot be entailed unless there are added statements, for example, about mediate experience and learning to educate the other not to be hurting others. In such a light Jeffrey is punishing Freda as a social act of education, albeit primitive.

If Freda's pulling Sam's hair in a hurtful manner that makes him cry is a deliberate act of hostile intention, carried out in indifference to, or even in pleasure in, the other's hurt feelings, and Freda's behavior cannot be traced back to previous mediating experiences, then this event would count as a disconfirming case with respect to the prediction (8).

Frida is living in a wartime nursery, deprived of family relations. She is 21 month old. I have observed and recorded, however, infants in the middle of their first year who actually hurt each other, albeit it is hard to say whether it is accidental or with intent. For example, Kine (5 1/2 month) and Silje (8 1/2 month), on the lap of Silje's mother, engaged in a kind of interaction which turned into a virtual wrestling match. As pointed out by Rubin, poking curiosity, rather than hostile intent, may be involved in such cases. Yet, if hostile intent was indeed involved in this "wrestling match" perhaps again some mode of protecting the closure might have been involved: Silje may have felt Kine to intrude or perturb the closure of Silje with her mother. In that case, the event concerns the boundary relations between the infant-adult dyad and a perturbing environment, even though the two infants were seen to be clearly interested in each other.

I have observed also how Katharina (15 1/2 month), a year after the incident when she comforted her older sibling, rejected a boy (12 months) crawling towards her sandbox. Even when he starts sobbing, she remains determined to keep him out her territory. When he goes after video-camera bag, which Katharina regards as hers, again she pushes him away. When he starts crying she does not come to his comfort. She does not attack him, but she clearly neglect to do anything about his distress. Now, Katharina lives in a family with four elder siblings, bring in friends all the time. She may have learnt to guard what is hers, and event to use force when necessary to keep intruders from taking what is hers.

Rubin (1980: 15-16) observes his son, Elihu (from eight months onwards) during sessions in his first playgroups. They include four infants - three of them still crawlers. The babies would tend to ignore each other, occasionally looking at each other with what seemed mild interest. However, there were isolated instances in which one baby approached and made physical contact with another, for example:

(ø7) "Vanessa takes Elihu by surprise by crawling to him, screaming and pulling his hair. Elihu looks bewildered. Then he starts to cry and crawls to his mother to be comforted."Z. Rubin, op.cit., p.15.

Rubin considers that such episodes of hair pulling, poking, and pawning by infants (eight or nine months old) did not appear to involve hostile intent. Instead, they seem to reflect the babies' interest in exploring one another.

There are, however, reports about mutual hostility between children, for example between first-borns and baby sibling during the latter's first year. Let us consider one such report.

Hostile behavior and understanding between siblings

In their study of sibling relationships involving loving and hating, understanding and envy, Judy Dunn and Carol Kendrick (1982: 4) point out that to consider the child and the mother as a dyad isolated from the other member of the family can be extremely misleading. They found that as early as in their second year, some of the second-born siblings exhibited a pragmatic understanding not only of how to comfort and console, but also to provoke and annoy the elder child. When six year old, several of the elder children (11 of 19) expressed verbally their dislike of the aggression of the younger siblings (between 42 and 60 months). One girl, for example, complains in this way:

"I don't like her; she is horrible, she is, 'cause uhm hits, disgusting; she shouts at me, hits me, kicks me, hits me."Judy Dunn and Carol Hendrick: Siblings: Love, Envy, & Understanding. London: Grant McIntyre 1982, p.207.

But it appears that occurrences of friendly and hostile behavior between siblings were dependent on how they got on with each from the early beginning. Dunn and Kendrick study 40 firstborn children living in Cambridge, England, with their mothers and fathers. They follow the children for 14 months after the birth of the second child in the family.They also include in their report a follow-up study of the children when they were about six year old. The above quotation is from that follow-up, conducted by Stillwell-Barnes. In cases where the relationships between mother and baby had been intense and playful, they find that six months later both children (the first born and the younger sibling who had been engaged in the playful infant-mother dyad) were particularly hostile to each other.ibid, p.175. A warm and friendly relation to the sibling, on the other hand, appeared to have been encouraged in those children who have a somewhat detached or conflict-laden relationship to their parents (Dunn and Kendrick (1982: 176). They find, for example, that in families where the mothers were depressed or detached due to tiredness during the first three weeks after the second birth, the sibling relationship developed in a more friendly fashion.

Depression or detachment on the part of the parent may have prevented this kind of mutual relations (Cf. Murray's study referred to in chapter 4). The newborn is ready to engage in interaction, inviting actual others to step into the companion space of its virtual other. If adults others are hindered from accepting this invitation, other actual others may come to respond. During the first month of life this involves an invitation to engage in such interplay in a mode of felt immediacy which both siblings will come to experience, and which will provide a foundation for later mediated modes of interaction.

Dunn and Kendrick also report that in families where the first child imitated the baby siblings frequently during the first three weeks, both siblings were particularly friendly to each other also 14 months later. Compared to the younger siblings in the sample, the baby siblings were on the whole significantly more friendly to their elder sibling who were reported to show interest and affection to the baby in the second and third week after birth, than those baby siblings who had not been met with such interest and affection from the first-borns.Dunn and Kendrick, op.cit., p.155-156. The first-born's response, in turn, to events surrounding the birth, turned out to be linked to his response to the baby's behavior towards him as an actual other, to his behavior in relation to the sibling 14 months later, and to his reaction to the mother-sibling dyad involved in play. ibid, p.6.

The first-borns, even those only two years old, showed a sensitivity to the emotional states of the baby sibling and an understanding of the baby's behavior that demonstrated their ability to feel (with) the actual other's perspective. This, again, is to be expected. According to implications of the thesis there is a natural ground, prior to cultural socialization, for the ability to feel with and take the other's perspective. Irrespective of whether it be furthered and hampered through the process of socialization, prosociality is entailed by the collateral to come natural to the infant. Even occurrences in extreme circumstances of intense reciprocal love-hate relationships can be expected, given a previous history of being hated or hurt.

The closure of six children from concentration campsAnna Freud: An Experiment in Group Upbringing, in: The Writings of Anna Freud. Vol. IV 1945-1956. I am grateful to Sophie Freud for this reference.

On October 15, 1945, six German-Jewish orphans arrived in Bulldogs Bank, in a nursery set up by the Foster Parents' Plan for War children. The children, about 3 years old, were victims of the Nazi regime. Their parents, soon after their birth, had been deported to Poland and killed in the gas chambers. As Anna Freud reports, none of them had known any other circumstances of life than those of a group setting. They were ignorant of the meaning of a "family". During their first year of life, after having been handed from one refuge to another, they arrived in the concentration transit camp of Tereszin in Moravia. There they were inmates of the Ward for motherless children until liberation in the spring 1945. They were then sent to a Czeck castle and given special care, before included in a transport to England.

Anna Freud reports how the six children insisted on being together and, at first, resisted any attempts to be separated or treated as individuals. At the same time they behaved aggressively and defensively, creating a shared front against the staff:

"During the first days after arrival they destroyed all the toys and damaged much of the furniture. Toward the staff they behaved either with cold indifference or with active hostility....

They would turn to an adult when they had some immediate need, but treat the same person as non-existent once more when the need was fulfilled. In anger they would hit the adults, bite or spit."op.cit., p. 168.

Within the group there were only verbal aggressiveness. They would quarrel endlessly at mealtimes and on walks, carrying out word-battles in German with an admixture of Czeck words. But the six children, with the exception of one child, did not hurt or attack each other during the first months. There was also an almost complete absence of jealousy, rivalry, and competition among the children. At the time, the adults played no part in their emotional lives. The children were extremely considerate of each other's feelings, helpful, showing concern and care:

"On walks they were concerned for each other's safety in traffic, looked after children who lagged behind, helped each other over ditches, turned aside branches for each other to clear the passage in the woods, and carried each other's coats. In the nursery they picked up each other's toys. After they had learned to play, they assisted each other silently in building and admiring each other's productions. At mealtimes handing food to the neighbor was of greater importance than eating oneself." (Anna Freud, with Sophie Dann, 1951).op.cit, p.174.

The above dramatic observations by Anna Freud and Sophie Dann may be described in terms of the postulated companion space of the children's virtual other. The six orphans are included in each other's companion space in a genuine sense of organizational closure. But during the first months, nobody but the six children were allowed to fill each other's companion space in a mode felt immediacy. The mutually constituted boundary excluded any other than the orphans from entering the companion space. Adult others were at first met with cool indifference or active hostility. They might be seen to threaten and perturb the auto-organizational closure mutually constituted and re-created by the children in concert.

Anna Freud reports that it was evident that they cared greatly for each other and not at all for anybody or anything else. They became upset when they were separated from each other, even for short moments.op.cit., p.169. One of the children did, however, from time to time withdraw from the group. This was Paul, who in his good periods was friendly, attentive, and helpful towards the other, always ready to take up arms against an aggressor. But when he went into his spells of compulsive sucking his thumb or masturbating, the whole environment, including the other members of the group, appeared to lose significance to him.

In terms of the present thesis, during such spells the actual companions were excluded from his companion space. His penis or thumb became a bodily medium for re-creating his own auto-organizational closure in conversation with himself, that is, with his virtual other.

Discussion

The group of orphans from the concentration camps may be seen to illustrate a very strong case of attachment to each other, even protective and loving care.

Even though precarious, the inborn ground for caring may even be brought to the surface against the extremely deprived and cruel background of concentration camps. As we have seen, Anna Freud and Dann report helping, comforting and caring behavior by three-year old children rescued from a concentration camp and deprived of any family life.But perhaps, as suggested by Sophie Freud, and told her by her aunt, considerations of these extreme circumstances prevented one from drawing the full theoretical implications of the reported observations by Anna Freud and hts on similarity across cultures in the high proportion of social and naturant behavior by 2- and 3-years old suggest such a natural ground. Some of their results suggested that negative social behavior may be traced back to cultural learning. Parents in certain communities were found, for example, to encourage their children to exhibit egoistic behavior in dominant and aggressive modes. Also the above report by George and Main on how abused toddlers engaged in abusing others, points towards an experiential ground for such behavior. When compared to children with no known background of abuse, children from an abusive family background are found in preschool settings to be more likely to be aggressive and less likely to help another child (Hoffman-Plotkin and Twentyman, 1984; Trickett and Kuczinksi, 1986).D. Hoffman-Plotkin and C.T. Twentyman (1984): A multimodal assessment of behavioral and cognitive deficits in abused and neglected preschoolers. Child Development, 55, 1984, pp.795-802;

P.K. Tricket and L. Kuczynski (1986): Children's misbehaviors and parental discipline strategies in abusive and nonabusive families. Developmental Psychology,22, 1986, pp.115-123. (Referred to in Harris, op.cit., 1989, p.37).

Harris (1989) proposes that differences in family background and cognitive factors go far in explaining the individual differences in hurting and comforting exhibited by children. Aside from family impact, he points out that children can be expected to differ to the extent that they can put themselves in the shoes of the other child. By virtue of their imaginative cognitive capacity they may appreciate both what led to the other child's distress and what might alleviate it, even when they themselves feels little or no distress (Harris, 1989: 39).

It follows from (q4) that the child is expected to feel, and hence take, the complementary perspective of the actual other in distress. But this capacity is naturally expected to vary with the way in which the child has come to experience and co-construct her world and others in it. The processes described in chapter 5 about how objects and language come into play, and re-presentations of others are con-constructed, will have an impact upon the way in which the individual child is able realized the above expectations.

Individual differences in the mediate capacity to simulated other (in line with domain (D3) of Fig. 5.3) has been demonstrated by Harris (1987) to have an impact upon children's individual performances in understanding emotional expressions.

He refers to studies by Stewart (1983) and by Stewart and Marvin (1984) which support the above explanation and which, moreover, may suggest the importance of individual cognitive differences in comforting behavior. In his study of sibling attachment in strange situations Stewart observed that when three- and four-year olds were left in the waiting room while the mother went in, about half of the older ones comforted the younger sibling who exhibited distress when the mother left. When submitted to tests on perspective-taking in imaginary situations, the majority of the children who did well on these perspective-taking tests were those who promptly had comforted their younger sibling in the left-by-the-mother condition.

Harris (1989:49) concludes from this and other studies that there is evidence showing that some children are better at taking another child's perspective and more ready to comfort another child as a result. This conclusion does not conflict with the present thesis. However, the capacity of taken the perspective of imagined others in imagined situations may have little to do with the capacity to take the actual other's perspective in an actual situation. Imagined test situations are different from the actual situations studied, for example, by Zahn-Waxler et al (1977). From studies of preschool children they find, as Harris refers to, that there is only an inconsistent or weak significant relation between prosocial behavior and perspective-taking.C. Zahn-Waxler, M. Radke-Yarrow, and M. Brady-Smith (1977): Perspective-taking and prosocial behavior. Developmental Psychology, 13, 1977, pp.87-88.

Harris, op.cit., 1989,p. 49-50, also refer to B. Underwood and B. Morre (1982): Perspective-taking and altruism. Psychological Bulletin, 91, 1982, pp.143-173, who uncover a weak significant relationship between perspective-taking and altruism, also when contribution of age is partialled out.

At the age of three, perhaps even before that, when the child has acquired the capacity to simulate actual others by virtue of working models (cf. the previous chapter), the child may very well engage in interaction with others in the mode of mediate understanding which does not entail any immediately felt reciprocity (Cf. domain (3) in Fig. 5.3). In such a modality, the actual other becomes an object of observation, reflection, and simulation. Hence, when engaged in such a mode the child should be able to take the other's perspective, not through felt immediacy, but through simulations mediated by his other-representation. Thus, taking the perspective of the other in this distant manner, and having learnt patterns of comforting, the child may be expected to comfort the other, even when not feeling the distress of the other.

Empathologic collapse

However, what is positively entailed by the present thesis is that there is, by virtue of the dyadic constitution of the child, an inherent capacity to take the other's perspective as felt, not as cognitively imagined, when in the mode of felt reciprocity. This may be seen as the primary ground for preschoolers' exhibiting care and concern. It also provides the ground for developing the mediate capacity to imagine the other in a cognitive simulated manner by virtue of models emerging in the child's companion space as the result of interactional experience. This interactional experience, however, may be so traumatic or perturbing that actual others may come to be excluded from this companion space, excluding immediate relations to others. For such an individual the secondary mode of relating to others remains, that is, imagining or simulating the other without feeling with the other in distress.

If the child suffers abuse or severe neglect, the child may come to resort to abusing or being indifferent to others. As mentioned in connection with the abused toddlers abusing other, this may come to evolve in two different ways. First, the child may resort to a path whereby actual others are excluded from the child's companion space in felt immediacy, and reduced to objects for manipulative abuse or indifferent neglect. There may, however, also evolve a path in which the neglected or abused child actively include the other in felt immediacy, so that hurting the other becomes hurting oneself, that is, one's virtual other, involving a communion through the inflication of shared pain. Neither of these paths are the only ones for the neglected or abused child. Even if the abused child has "learnt" the role of the abuser, by virtue of its inherent dyadic constitution, enabling it to feel the abuser's perspective, in the abused child there is still an inherent ground in the abused child for coming to exhibit tenderness and concern for the other. While precarious, it may come to unfold itself even in the most deprived circumstances. The patterns of abusing the other or showing cool indifference to the other's being abused, stem from experience and may involve empathologic collapse brought about by the environment. The above abusing toddlers who themselves had been abused or neglected came from families partly deprived in parental or economic respects. As we have seen, however, even the children coming from the uttermost extreme of deprived conditions, having lost their parents in extermination camps, showed themselves capable of caring for each other.

Individual experiential differences

In his work on children and emotion, that covers his own empirical studies of emotional understanding, Harris (1989) has reviewed a number of studies, including the above by Judy Dunn and her colleagues at Cambridge. He has examined possible explanations of individual differences in children with regard to comforting and hurting. With reference in particular to a study by George and Main (1985) he concludes that capacity for concern is not an inherent capacity.

I have considered carefully the explanations proposed by Harris of patterns of children comforting and hurting others, or showing indifference to others being hurt. I accept his explanation of individual differences as resulting from differences in experiential background and in the capacity to cognitively simulate others, which also presuppose, as we have seen in chapter 5, an experiential ground. I submit, however, that there is "chemistry" involved in the infant's caring for the other, like the felt immediacy which the parent or careperson sometimes engage in when caring for or comforting the baby. Thus, mediate understanding of emotions is not a mere exercise in cognitive imagining oneself in the other's shoes. I define a perspective as felt. The process of taking the actual other's perspective in a concrete situations cannot be entirely divorced from feelings. Even though a perspective may be conceived as a cognitive undertaking stripped of feelings. A perspective involves the others and the world as felt, not merely reflected upon. Hopefully, further research will clarify the relations between taking the other's perspective through the kind of mediate understanding that involves mental simulations, and the kind of immediate understanding that involves felt reciprocity. I concede that there are experiential grounds for individual differences in the unfolding of the capacity to take the other's perspective, but hold that there is an underlying cross-cultural ground for relating to the other in felt immediacy.

With regard to the ground for hurting, then, I agree with Harris's conclusion that hurting and abuse stem from an experiential background. If such behavior is found not to stem from such personal histories of abuse, or not to emerge from some pathological ground, it would entail that there is something wrong with the present thesis or its collateral assumptions. Hopefully, this may become clearer through further research. True, hatred may be involved in a reciprocal mode of felt immediacy. But deliberate hurting in a care-less, indifferent manner cannot be seen as involving a reciprocal mode of felt immediacy, unless it means hurting oneself (that is, involving one's virtual other) as well. When aggressive behavior directed at the actual other can be seen to be reaction against perturbation of dyadic closure, it may be related to the present thesis. Cool, indifferent "cold-blooded" hurting behavior on the part of the child, however, is precluded by the above entailments of the thesis as stemming from an innate ground. While anger, and even hatred, may be considered modes of felt immediacy, and, hence, belong to the domain of implications, reports on deliberate infliction of pain on the actual other in an indifferent manner would be pointing in a disconfirming direction, unless they could be shown to be related to previous experience, for example, of being abused.

In line with the thesis I submit that there is deep dyadic structure underlying the patterns of comforting and caring which does not derive from experience, even if it is modified, perturbed, or even brought to collapse by what the child may come to suffer, and hence, indirectly also may show itself even in abusive behavior, for example, in the way the child may be hurting itself though using the other as a medium in the self-organizing process.

Harris and others draw attention to the way in which children hurting other children, or being indifferent to others being hurt, may be related to environmental impact, such as prior experience of having been abused or neglected. This is also consistent with entailments from the present thesis, albeit qualified in this way: There is a difference between hurting the other through what I have termed empathologic collapse, treating the other as a prey, and inflicting pain on the actual other replacing the virtual other as a way of punishing oneself in felt immediacy. Both kind of patterns may be found to be brought about by previous environmental experiences of being hurt, abused or neglected. But each pattern comes about through a different mode of relating to the actual other, in the first pattern being excluded from the child's companion space, in the second pattern being included.

Divorcing the virtual other

There is an apparent causal asymmetry between hurting and comforting. Comforting presupposes that the comforted one has been hurt, and comes about, as a spontaneous offer, by virtue of the comforting child's feeling the perspective of the hurt one. Hurting someone comes about by the hurter having been hurt, and will, unless there is empathologic collapse in the hurter, elicit in the child engaged in the hurting the complementary feelings of hurt and concern.

By "empathologic collapse" is here meant that the capacity to feel for the lifeform of the other has been perturbed in such a way that the actual other is excluded from the companion space of felt immediacy by virtue of some command or control logic (Cf. the Greek roots en + pathos for in + feeling, and pathos for suffering). This may apply to some hunters' relation to a prey. Feelings of excitement and fear of destruction may arise in the hunter. But there may also be empathologic collapse reducing the prey to an object for anticipatory simulations.

George and Main (1985) have observed children, between one to three years of age, coming from families in several of which fathers were absent and mothers were living on welfare. Some of the toddlers had been abused. In their observations, these abused toddlers were never found to express obvious concern for another child in distress. Sometimes, they even tormented the other child until it began crying and then, while smiling, mechanically patted or attempted to quieten the crying child.Carol George and Mary Main: Social interaction of young abused children: Approach, avoidance and aggression. Child Development, 50, 1979, pp.306-318.

One of the critical episodes that Harris refers to in their report is this:

"In some of the most disturbing incidents (involving three abused toddlers) an alternation between comforting and attacking the distressed child was seen. For example, one toddler pursued and tormented another child precisely until the child exhibited distress, and then mechanically comforted the child, smiling at the same time." (Harris, 1989,:38)Harris, op.cit., 1989: p.38.

Harris concludes that empathic concern for the other's distress "is not ineluctably wired into the emotional repertoire of a young child."Paul Harris: Children and Emotion. Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1989, pp.37-39.

According to the present thesis the capacity to invite the other into one's companion space in felt immediacy is an inborn, and yet precarious capacity which may be perverted and transformed through socializing and social experiences with actual others who reject this invitation or abuse the child. The report on toddlers' engaged in abusing another child permits two different interpretations in terms of the present thesis. First, the abusing toddlers may include the victim in their companion space for lived moments of abuse in felt immediacy, as they themselves have previously experienced, or, second, the previous abuse may have led to their companion space being encapsulated, excluding actual others from entering. In the first interpretation, when tormenting and quitening the other, the abused toddler is also tormenting and quietening himself, that is, his virtual other. In the second, the victim is excluded from the companion space, transformed into an object for mechanical play, or a prey to the hunter in empathologic collapse, brought about by the abuse that the toddlers have experienced.

Circumstances may bring about a temporarily or more or less permanent conversion of the inherent capacities postulated in (q). Here was postulated that there is an innate companions space in the dyadic organization of the mind for dialoging with a virtual other that invites fulfillment by some actual other in a modus of felt immediacy. In the light of what has been considered above, we may now express the ultimate collapse of the primordial form of the dialogical:

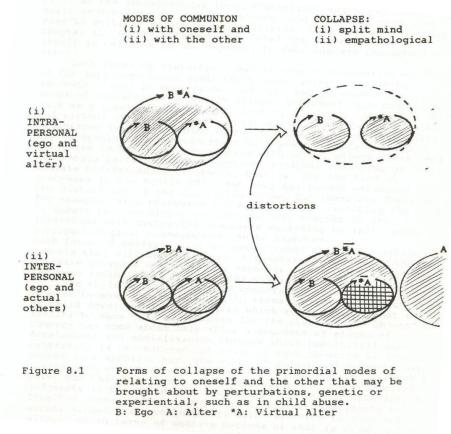

(p2) Perturbing biological, psychological, or social conditions may come to bring about, temporarily or more or less permanently, (i) a divorce between the self and the virtual other, preventing the otherwise natural self-organizing dialogue from realizing itself in the mind of the individual, or (ii) an encapsulation of the companion space of the virtual other, preventing actual others from being included in that space in felt immediacy.

At the intrapersonal level the above may manifest itself in a split or divided mind, in the extreme case abuse may even give rise to multiple selves or personalities. This will be returned in chapter 12. At the interpersonal level the above may manifest itself in collapse of the capacity to feel concern for the other. These two forms of collapse of the original dyadic and reciprocal nature of the mind, brought about by genetic or experiential distortions, are indicated below.

The above diagram indicates in a schematic form the proposition led up to above about how perturbations of various kinds can bring a more or less permanent (i) divorce from the virtual other *A, or (ii) encapsulation that prevents actual others A from being included in felt immediacy. The latter need not preclude transitional-like dedication to some ideological cause or collectivity C that may provide lived moments of communion with the cause or the collectivity as an actualized other.

Thus, dependent upon conditions, such as a genetic disorder or a history of abuse, the mind's self and virtual other may come to split apart, preventing the self-organizing dyad of the mind to realize itself internally, while the encapsulated companion space will prevent it from being recreated in immediate reciprocity with actual others. This does not entail that there need be perturbations in the capacity for rational reasoning or for mediate understanding of others, that is processes in the domain (D3). Nor is entailed that such consequences need be enduring. They may involve a temporarily collapse of the self-organizing dyad, which again later may come to recreate itself in accordance with (q), and as complements to modes of mediate reason and relations.

In (p2) the term "or" is used in the inclusive sense of and/or, not as "either-or". The above terms for the kind of consequences referred to, when classified as pathological, are translatable into various clinical terms, dependent upon the actual theory frame evoked. "Dissociation" is a weak term for consequence (i), while "schizo"-terms more strongly suggest pathology. I propose the term "empathologic collapse" for consequence (ii).*) empathy n the ability to understand and imaginatively participate in the feelings or ideas of another person. < Greek en - in + pathos feeling.

pathological n < ultimately Greek pathos suffering + logos word. (The Penguin Wordmaster Dictionary, 1987:229;505)

*) In chapter 10 we shall see how both aspects may apply to persons who are not attributed pathological labels, even though their monstrous acts are far from the normal acts in the life of everyday individuals. This involves the converse of the caring capacities in the very young that have been indicated in the previous chapter.

The child's ability to show concern may appear to run counter to what can be expected in terms of conventional theories of child development according to which it is assumed that the ability to show care and concern for the other as an "object" of concern can come about only after a sequence of stages of development and socialization through which the initial ego-centricity is de-centered, at least if such theories is interpreted in a specific way. The works of Piaget and Kohlberg may invite such an interpretation, albeit Piaget has been careful to point out that his theory of moral development concerns moral judgments in the child, not sentiments. The entailments derived from the present thesis, in contrast, concern sentiments in actual situations, not judgments with reference to imagined situations in terms of mediate notions of what is right and wrong. Such contexts for moral judgement and moral dilemma-processing will be taken up in the next chapter.

TO SEE THE INDEX OF TEXTS IN THIS SITE, CLICK HERE