Chapter 2

Perspectives on Infant-adult Interplay: Quest for Explanation

Infant researchers disagree on this issue: to what degree do the observed patterns of protodialogue and imitation in infancy reflect infant abilities? Perhaps such patterns are merely or mostly the outcome of the adult's communicative and anticipatory skills. While Schaffer, for example, considers the infant an asocial being to begin with, and doubts its ability to imitate, Bower regards the infant as born a social being, and Trevarthen considers it proved that it is able to imitate. He regards protoconversation as indicating a primary intersubjectivity on the part of the infant, while Newson, Chappell and Sander consider the phenomenon to reflect the parent ability to treat the infant as if it were a partner in dialogue. For example, as Newson (1979:208) states it, "babies become human beings because they are treated as if they already were human beings".

In this chapter I shall succinctly review some interpretational views on infant-adult interplay. First, we shall see how it may be considered in symbolic terms of the linguistic and cultural background which the adult brings to bear on the process, and to which the infant is partly a newcomer. This perspective invites explanations in terms of the adult in control through symbolic representations, or also in terms of the infant's schemata as they are brought to bear upon, modified, or generated in the process of "scaffolding" (Bruner,...; Neisser,....;Newson,...).1

Second, the infant-adult interplay can be regarded in the psychobiologic terms of the neurophysiological structures that bodily realize the observed phenomena. This perspective invites focusing upon the biological and self-regulatory boundaries and mechanisms of the neurophysiological structures of the participant organisms.

And third, I shall introduce the perspective of dyadic closure upon the infant-adult interplay. Supplementing the other perspectives, it invites considerations of the way in which the observed patterns are generated by a self-organizing dyad, and permits a specification, to be turned to later, of how the infant and the adult actively and effortlessly are able to partake in such

a self-organizing dyad (Bråten, 1988a).

Control through symbolic representations

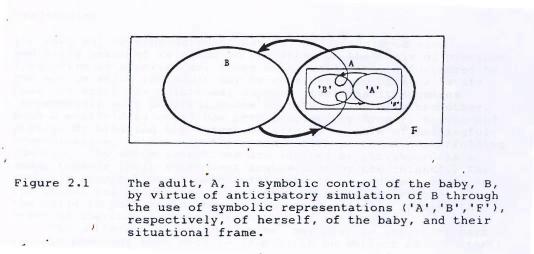

The mediating means and the cultural history which the adult brings to bear in her interaction with the neonate, may be seen as necessary conditions for the control that the adult may exercise and the process whereby the infant gradually comes to acquire the key to the storehouse of linguistic means and cultural history which the adult brings to bear on the interaction. The adult-infant dyad is viewed from the perspective of the adult in symbolic control, simulating the other (Bråten, 1973ab, 1988a). The adult's background experience may even be seen to provide the means for anticipating the reactions of the baby in a way that appears to the observer as if the infant is doing the imitation. That which is attributed as the infant's imitation might be seen to come about through the adult's power of anticipating and simulating the infant's behavior by virtue of the adult's representations. The adult may be more or less in control of the process by virtue of the representational schemata which she has of herself and of the baby and the background knowledge and cultural history which she brings to bear on the process. She uses the representation of herself, 'A', of the baby, 'B', and of the situational frame to knowingly anticipate and replicate the (re)actions and reconstruct the intended movements of the baby. This is grossly indicated below (Fig.2.1).

By virtue of her knowledge mediated by internal "simulations" with such symbolic representations of the relations between herself and the baby, the adult is sensitive to the sounds and movements that the baby is going to exhibit in such an anticipatory way that the adult may actualize them before they occur, and then take her turn to imitate them after they have been realized by the baby. For example, as the child prepares herself with waving arms to open its mouth and emit "cocooing sounds", the adult may already do so in advance of the baby's cocooing. To the observer, this may appear as if the baby was imitating the mother's opening her mouth and cocooing, while it may occur as the result of a process in which the mother is in control in virtue of her power of predicting and postdicting the other's turn.

In the extreme variant of the adult in symbolic control, the baby may be seen as lacking any autonomy and serving as an instrument played upon by the adult. The adult is able to covertly predictively simulate the other's reaction and postdictively reconstruct the other's "intention" as means of controlling the overt interplay, as it appears to the observer. Hence, as long as the child is regarded as an instrument to be played upon, with no independent autonomous resources of its own, that which appears as synchrony and perfect tuning, would be the outcome of the adult's playing, much as the musician with his saxophone or piano playing exhibits a perfectly coordinated pattern.

In the above diagram the infant is left unspecified, as if the infant takes no active parts whatsoever. But even the newborn is no tabula rasa. There have been experiences in the womb of the mother's body and of sounds in her environment, and during post-natal interaction, there are new experiences to be reacted upon. There is the familiarity of the smell of the mother's body and of her milk, familiarity of her voice, perhaps already at birth, and later of the face of the caretaker that engage in recurrent interaction with the child.

Scaffolding

The baby may be considered to have already developed some mediating means of relating to the other on the basis of previous interactional experiences. These means will come to furthered by the way in which the adult may be considered to offer a "scaffold" on which the infant may support itself as it acquires increasingly more powerful means of interacting with the other. Such a scaffolding model has been proposed by Bruner, Newson and others. By treating the infant as already capable of meaningful communication, mothers in this perspective performs a scaffolding function, "by which intentions are imputed or attributed as a stage towards their subsequent acquisition by the infant".2 The mother's attribution of meaningful intentions and capacities to the child, and responding accordingly while in control, enables the child to partake in the process, and gradually acquire the means of sharing in the co-ordination of the process.

The pattern labeled "imitation" may play in important part in this process. When mothers from birth on reflect back to their infants gestures and vocalizations which the infant has produced, and insert their own copy of the infant's production into a sequence of his repeated responses, and then greet with delight the similar response that appears as an imitation, certain productions by the infant will be endowed by communicative significance (Schaffer, 1984). Clearly, scaffolding can be seen to play a significant role in the process of cultural and linguistic acquisition of mediate means for communication. From this, proper replication of linguistically significant productions may be expected to be stimulated, as part of the process of entering through protoconversation, the gate to a common language horizon. This calls for the complementary account in terms of the cultural heritage and linguistic means of representations which the adult brings to bear on the process, considered in the domain of the adult in control of the process or as providing a scaffolding function.

In terms of the scaffolding model the very process by which the mother or another adult treats and responds to the infant as if the baby is capable of mutual understanding and reciprocal relations, is seen to provide the mechanisms through which the child becomes capable of mediate understanding and reciprocity (Cf. for example, Bruner;...; Chappell and Sander, 1979; Newson, 1979). There is an initial asymmetry in terms of symbolic capacity and control which, by virtue of scaffolding, may be seen to pave the way for the more symmetric modes of symbolic interaction to emerge later.

Symmetry in peer interaction?

A certain symmetry appears to be manifested fairly early in peer interaction. Verba, Stambak and Sinclair (1982) study interaction between children of 18 to 24 months of age. They appear to be carefully observing each other, sometimes addressing the other, for example by offering objects to the peer as an invitation to join in a common activity. When seated around a table with objects placed on the table top, the action of one child may be taken up by another, or by several others. The children observe one another, and complement each other's actions with these objects (albeit more rarely). During a long period they all transform the initial action into an intricate sequence of related activities whereby the participants contribute through a process of imitative and creative interaction of the modifications of the initial action. The investigators report a case where they "struck by the fact that a child "understands" the problem with which another child is dealing even if that other child does not succeed in solving it. He shows this understanding by demonstrating the right solution after using a stratagem to the gain possession of the necessary object." (Verba et al, 1982: 293).

Schaffer (1984: 153-154) reviews other studies of peer interaction between children at a somewhat later age and concludes that they exhibit the coherence of a "proper" conversation. The children are able to alternate their remarks in an orderly fashion, each waiting for the other to finish before starting his own utterance, which imitates or expands upon the utterance made by the other. This patterns is exemplified by a reported exchange between twins, 33 months of age. Now, at this age the children will have a rich repertoire of interactional experience to draw upon in their developing symbolic means of representing and simulating the other in a proper conversation of mediate understanding. Their capacity for "proper conversation" may well have come about through earlier experiences of being scaffolded during infant-adult interplay.

But then, even during the first months the infant may be also be exposed to other children as interaction partners whose behavior hardly can be laid out as scaffolding. I have observed and videorecordet interactions between infants of unequal age (two month and two years). In some of the recordings between a younger and elder child I find indications of affect attunement and reciprocity. There occurs also vocalization in unison. I do not, however, find to patterns of finely synchronized protoconversation between children of different ages. Usually, the older one of the children is "running the show", sometimes impatiently, perhaps aware also of the adult observer by the camera. While the baby take pauses in her sound productions, and will listen to the elder child, the latter does not often stop in her vocalization and listens to the baby. Even when the elder sibling does not pause to listen to the baby, the baby clearly shifts between making sounds and listening to the other. A three months old infant, for example, appears to be patiently inviting the older child to engage in mutual turn-taking, but the older rarely complies and may instead be giving a performance directed at the adults present.

Attributing a theory of mind or a working model to the infant

The opposite of the view of the adult in complete control is the view of the infant's entertaining a theory of mind (Fodor, 1987; Ashington et al. 1988). The infant is seen as able to attribute believes and desires to the other, and to explain and anticipate the other's behavior in terms of the infant's theory, parts of which are innate, parts as developing during interaction.3 In functional terms, aside from the attribution of innateness, this relates to Mead's attribution to the child of a generalized other, by virtue of which the child is able to anticipatory simulate the other's reaction (Mead, 1934; Bråten, 1973). While taking exception to the view of children having a theory of mind, Harris (1989) considers their imaginative capacity to be such that they can indeed simulate the intentions and emotions of another person.4

Daniel Stern (1985) also attributes to the infant a working model of the other, emerging on the basis of generalized previous interaction experiences and mediating the understanding of the other. The generalized subjective experiences of the child and of the mother are being bridged through mediated and generalized interactional experience. For each of them, the subjective experience of being with the self-regulating other involves the activation of the evoked companion of each of them on the basis of the working models of others which they have formed through representations of past interactions that have been generalized. I shall return to Stern's model in chapter 7, devoted to mediate understanding. But before considering the emergence of mediational means of understanding we have to consider the way in which the initial understanding can come about that paves the way for generalization of experience and the genesis of re-presented others. We have first to consider, among other things, emotional reciprocity and the amazing capacity for a-modal perception of the other's affect expressions, stressed by Stern. Can Naseeria, for example, born before term, who is in communion and duet with her father, already be attributed a working model of her father? She is not quite without prior interactional experiences. She is three weeks old when the videorecorded episodes of gazing and smiling interaction occur, and six weeks old when they engage in a turn-taking duet. But this still occur six weeks before term. It is difficult to conceive of their reciprocal gestural, visual, and auditory interplay as mediated by representations in the baby. Even if her father performs scaffolding, there appears to be genuine reciprocity.

Attachment, symbiosis, and felt immediacy

Prior to the formation of any constructed or generalized other, there is already at birth a remarkable readiness to immediately relate to the other's feeling. Newson (1979), for example, stresses as we have seen, those "mysterious processes" which underlies the baby's capacity to share states of feeling with an actual other.5

Rom Harré (1983: 104-105) speaks about psychological symbiosis in the symbolic sense of people completing each other in public activity. He considers the infant-adult dyad as a single social being, and points out that its internal relations need not be specified; it may exhibit social interaction even though only one of its constituent participants has the proper abilities and power. This is consistent with the symbolic control perspective upon the infant-adult dyad as being asymmetric in such mediating respects.

There is also a certain asymmetry ascribed to the infant-mother pair in the control-theoretic terms that Bowlby applies to mother-child attachment. The goal-directedness of the mother as a control system is more developed than that of the child.

Bowlby offers a richness of empirical insights into mother-infant attachment.6 He considers attachment behavior in some degree to be preprogrammed and therefore ready to develop along certain lines when conditions elicit it.7

He develops his original thesis about attachment in terms of control systems in which appraisal processes are felt as a phase of the processes themselves.8 Being felt, he stresses with Susanne Langer,9 is a phase of the process itself, not a product of the process which the noun "feeling" may invite one to assume.10 Attachment is seen as mediated by the organization of control systems, the mother as a goal-corrected system and the simpler control system of the child.11 The child's signalling behavior and the mother's approach behavior make for attachment.12 The initial smiling and babbling on the part of the baby is not seen as goal-corrected, but emitted as signals from a control system that have immediate effect on the behavior of the adult goal-corrected control system. The organization of both systems mediates attachment permit the respective signalling and approach behavior that make up attachment. In this manner Bowlby is able to account in operational terms of two control systems of how such attachment emerges from preprogrammed tendencies and situational elicitation of specific interactional behavior.

Bowlby stresses the potential of the healthy newborn to enter into an elemental form of interaction and the potential of the ordinary sensitive mother to participate successfully in it and be quickly attuned to her infant's natural rhythm. The infant's initiation may follow his own autonomous rhythm, while the sensitive mother through skillfully interweaving her own responses with his creates a dialogue. There is mutual enjoyment as it develops in precise synchrony though the adult's modifying her own response in a goal-corrected control systems manner to suit the infant.13

In object-relations theory, to which I shall return in chapter 4, the dual infant-mother unity is attributed asymmetry. The pair is described in terms of symbiosis, with the mother considered to be the leading part and the infant lacking contact abilities. Hence, a strong asymmetry is ascribed to their interrelation. In this respect the object-relation theoretic notion of symbiosis relates to the asymmetry assumption of the scaffolding model. But there is this difference. The notion of symbiotic unity entails that the relations are internal to the dyadic union of mother and child, not external mediated by symbolic exchange between externally coupled individuals. As complementary to the domain of symbolic mediation this opens for a domain of felt immediacy in which the feeling and understanding that arises in the infant-adult dyad are seen be immediate or direct in a primary sense.

Primary intersubjectivity and alteroception

Detailed analyses of recordings of young infants, less than three months old, capable of engaging in "protoconversation" with their mothers, seem to indicate a kind of primary reciprocity in an immediate sense. The exhibited reciprocity and finely tuned complementarity and follow-up of sounds and movements in turn-taking, point to an innate readiness in the human baby to relate to another human being, and more than that, an innate capacity for the beginning of intersubjectivity in the form of interpersonal and cooperative understanding.14

Trevarthen has devoted much of his research to the development of intersubjective motor control in infants from a psychobiological perspective.15 He regards the remarkable precocity of newborns for emotional and expressive communication with the adult other as an indication of an inborn capacity for intersubjectivity.16 This is defined in terms of coordination between evolving states of attention, emotional change and cognitive adjustments in two intending beings, which involves coordination of intended actions even before they are executed. He introduces the notion of alteroception for the communicative awareness that depends on specific cerebral response to the kinematic, energetic and physiognomic aspects of body movements that inform about intentions in the other subject:17

"As with the prereaching movement aimed to a thing moving outside the surface of the body, selecting one location in an exteroceptive reaching space that maps onto the whole motor coordinative mechanism of the body (and its proprioceptions), the expressive movement of another person serves as a goal in an alteroceptive or intersubjectivity space. A stimulus of that kind maps onto a motor coordinate mechanism representing, not only the output of communicative expressions of the infant as subject, but also, separately, the invariants of stimulation in an input of expressions from another subject. This is the basis for all intersubjective coordinations, including imitations.."18

Trevarthen proposes to see imitation, even in the newborn, in the above quoted terms as a special case of communicative identification or mirroring, in which each subject comes to carry out a sequence of functions that represent the changing states of interaction between himself and the other. There is no need to assume that the infant has to acquire a 'representation' of the other19 in order that this be accomplished: "Somehow the infant mind is ready to behave in the space between itself and another person".20

The closure of the self-organizing infant-adult dyad

The challenge, then, is to specify the organization that emerges in this space and generates protoconversation and the accompanying patterns that to the observer appear as imitation. The findings of the infant's ability to engage in protoconversation appear to be at odds with Piaget's view of the infant as initially (ego)centric, unable to take or share in the perspective of the actual adult other. His theory of cognitive development concerns the infant's elaboration of new structures and new lines of conduct in the course of a constantly constructive development of its own auto-regulative organization. Evoking a metaphor from the geometric domain, one may say that according to Piaget's view there is an (ego)centre of the self-enclosed circle of the baby B with the adult (alter) A outside or in the orbit of this circle.

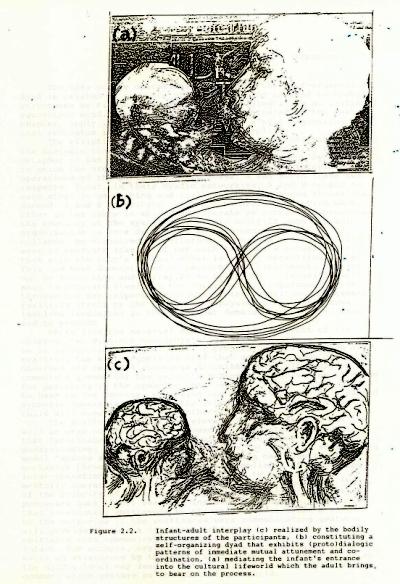

The alternative scheme that I propose retains the notion of auto-organizational closure. But it requires that the centric circles of distinction between B and A be replaced by another form: Replace the circle by an ellipsis with its two generative foci, B and A. Regard this as an autonomous system defined as a dyadic unity by the bifocal organization that makes A and B the two participant processes of a dyadic network in which they, through their reciprocal inter-operations, constitute the elliptic boundary that emerges in the space in which they inter-operate. This is indicated below (Fig. 2.2 (ii)).

The idea of the operational closure of the self-organizing dyad is related to the idea of autoregulation applied to mental structures by Piaget. But rather than applying it to an initially egocentric mind, I shall, as will be demonstrated in the nest chapter, apply it to the infant's mind as a self-organizing dyad that recreates itself in infant-adult interplay.

The elliptic metaphor permits a preliminary definition of the dialogic closure of a dyadic system, not merely in the metaphor of the curve that folds back on itself, but by the way in which the organization is characterized by the interlaced operations of the participant processes, A and B, in these two respects: First, in their dyadic networking, A and B depend on each other in generating and realizing the processes themselves. Second, A and B constitute, by their mutually completing each other in the space in which they operate as interlaced processes the boundary of the system as a dyadic unity.21 Such a dyadic organization is here defined as an autonomous system. It may collapse, be dissolved or perturbed. When this occurs, it will seek to recreate itself, if not with the baby's actual other, then with the baby's virtual other in a self-organizing manner. This has been demonstrated in perturbation experiments carried out by Trevarthen and Murray,22 to be turned to later. It will seek to recreate itself at the inter- or intra-personal level through the participant operations of its constituent processes, realizing itself by the bodily neurophysiological structures involved (indicated in the uppermost domain of Fig. 2.2), Thus, and to provide

While from the material and structural viewpoint of the observer two distinct neurophysiological structures are seen to be in interaction (Fig.2.2 (c)), I propose to consider them as realizing the self-organizing dyad that generates some of the observed and recorded phenomena described above. It provides the immediate ground for the infant's subsequent acquisition of means for partaking in the symbolic (back)ground that the adult brings to bear on the process, mediating the co-construction of a shared symbolic domain (a) in which the interactionally experienced child will come to exist with others.

The scaffolding model is relevant in this respect. But it will be seen to presuppose a ground of immediate understanding that facilitates the acquisition of symbolic means for mediate understanding. Bremner (1988:199) points out that the scaffolding model "smacks a little of magic" unless one can identify the mechanism through which the feat is accomplished of permitting inter-operations accomplished by the dyad to become intra-mentally operative in the infant. Referring to Vygotsky's theory of the priority of inter-psychic processes over intra-psychic processes Lock (1980) searches for such a mechanism. He suggests that involuntary emittances by the infant which evoke a respons by the mother as if the emittances were communicating gestures, will provide the basis for the transformation of such types of emittance into communicative gestures also on the part of the infant. For example, crying as an involuntary emittance will evoke an attendance by the adult though which the interaction at the dyadic level may lead to internalization of crying as a communicative gesture on the part of the child.

But again, it is a tremendous feat for anyone, not least the infant, to be able to transform initially asymmetric and non-reciprocal events in the dyad, treated by the other as if they were symmetric and reciprocal, into internal operations that may come to invite reciprocity in the future. That is, unless there already be in operation in the infant an inherent reciprocal dyadic organization. This is precisely what I shall suggest. But then, as I purport to show in the next chapter, by virtue of such an inherent organization of the mind there is already a ground for inviting immediate reciprocity in the first place, and no need for assuming the above asymmetric transforming operations.

E031291 NOTES TO CHAPTER 2

1Specify references to Bruner, Neisser, and Newson on scaffolding model...also ref.5....

2Newson....., 1979, pp.94-95.

3J.A. Fodor: Psychosemantics. Bradford Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1987. J.W. Ashington, P.L. Harris and D.R. Olson: Developing Theories of Mind, Cambridge University Press, New York 1988.

4Paul Harris: Children and Emotion, Basil Blackwell, Oxford 1989, pp.2-3.

5Newson,....1979, p.91

6J. Bowlby: Attachment. (Attachment and Loss, Vol. I). Harmondsworth, Penguin 2nd ed. 1984.

7J. Bowlby: Caring for the young: Influences on Development. In: R. Cohen and B. Cohler (eds.): Parenthood. New York 1984, pp.269 - 284.

8J. Bowlby: op.cit. 1984, pp.108 - 110. Bowlby refers to S. Langer 1967............

9S. Langer: Mind. An Essay on Human Feeling. Baltimore: The John Hopkins Press 1967.

10This is consistent with the way in which the term "felt" is used in the expression in terms of the present thesis about "felt immediacy". But there is this difference: To Bowlby, the processes as felt are phases of control systems appraisal processes, mediated in terms of control systems goals.

11J. Bowlby, op.cit., p.251.

12ibid, p.244.

13J. Bowlby, in Cohen and Cohler, op.cit. 1984 p.273.

14C. Trevarthen: 'The Foundations of Intersubjectivity: Development of Interpersonal and Cooperative Understanding in Infants', in: D. Olson (Ed.) The Social Foundations of Language and Thought, Norton and Co., New York 1980, pp.316-342.

15C. Trevarthen: 'Development of Intersubjective Motor Control in Infants', in: M.G. Wade and H.T.A. Whiting (Eds.) Motor Development, Martinus Nijhoff, Dordrecth, 1986.

16C. Trevarthen: 'Development of Intersubjective Motor Control in Infants' in: M.G. Wade and H.T.A. Whiting (Eds.) Motor Development, Dordrecth, Martinus Nijhoff, 1986.

17C. Trevarthen, op.cit., 1986.

18Reference to Trevarthen....

19Trevarthen, like Stern, has previously resorted to notions of representation: "More commonly the represented 'other' will be acting in complementary way to the represented 'self', and the expression of the self will augment and complement the expression of the other." (Trevarthen, op.cit., 1986). Recently, he has moved away from an information processing account in terms of representations.

20C. Trevarthen, op.cit., 1988, p.13.

21This definition may be compared to Maturana's definition of autopoiesis, pertaining the individuals realizing their autonomy through structural couplings in the media in which they live. The difference, however, is this: Above such autonomy is attributed to the protoconversational dyad. This is in line with Pask's conversation theory, and Varela's related treatment in his Principles of Biological Autonomy. The operational notion of the virtual other, to be turned to in the next chapter permit me to attribute the same reciprocal dialogic organization to each of the individuals in solitude: the same dialogic auto-organization will now be seen to realize itself though an internal dialogue that involves a virtual other, instead of the actual other.

22Cf. Lynne Murray: Winnicott and the Developmental Psychology of Infancy. British Journal of Psychotherapy, Vol. 5 (3), 1989. pp.340-342. The Trevarthen-Murray perturbation studies will be returned to in chapter 4.

TO SEE THE INDEX OF TEXTS IN THIS SITE, CLICK HERE