Chapter 14

How can there be Interpersonal Coordination in Time?

In observing human dyads, be it protoconversation between infants and adults, or intimate conversations between adults, one is often struck by the inter-bodily matching and coordination of gestures that are exhibited. When one asks for the minimal characteristics of an infant-adult protoconversation (as we did in chapter 3), or of the primordial dialogue between intimates, temporal aspects enter into the observer's characterization that may differ1 from the lived moments of time by the participants. First, any kind of conversation will be seen by the observer to involve turn-taking, for example, between questions and replies, uttered in response to past questions, and perhaps, in the anticipation of future ones to come.

Second, a dialogue involves at least two different perspectives in conversation. As long as there are different complementary or crossing perspectives involved, even smalltalk or a conversational ritual confirming the social cohesiveness of the participants may allow for the emergence of novel insight or Aha-experience.

Third, in order to engage in a mutual co-operative undertaking, the participants somehow have to be contemporaries, in other words, to co-exist in each other's present, engaged in an intersubjective phenomenon that involves the actual other here and now. While entertaining complementary perspectives or frames, they somehow appear to share a present "here and now" (Rommetveit, 1974).

Fourth, intimates in dialogue will sometimes exhibit inter-bodily coordination and attunement with the matching of small movements that require slow-motion video-replay or frame-by-frame analysis in order to be captured by the observer. Some observers (Condon and Zander, 1974; Bower, 198?) have reported infant-adult dyads to exhibit what they term "interactional synchrony". But as pointed out by Stern (1985:84), this has been difficult to

demonstrate in replicate studies. When there is not vocalization in unison, the turn-taking pattern appears to be more prevailent. Such patterns may be described in terms of observer's time. For example, when analyzed frame by frame, or on a continuous scale of nano?)seconds, Trevarthen finds infant-adult dyads in protoconversation to exhibit a finely tuned dialogic dance, involving turn-taking to the split second, without any collision of noise or gestures.

Such a description in observer's time applies to the pattern exhibited by the dyad. But were we to apply the descriptions in an account of how this pattern is generated by the dyad difficulties may arise. We could envisage, or even try to simulate, the dyad participants as two observers, each with a timeclock on hand or in the body, who externally timed their reciprocal gestures in an effort to achieve mutual coordination. But the immediacy of their reciprocal gestures of mutually completing each other as members of a self-organizing dyad would escape such an attempt. In a ping-pong match, for example, if one of the players were to consciously monitor his adjustments during the game, he would be in trouble. Harth (1982) and Penrose (1991)2 refers to experiments that suggest that a conscious adjustment may require more than a second to come into play, and perhaps another second to take effect (Deeke et al., 1976; Libet et al., 1979).3B. Libet, E.W. Wright Jr., B. Feinstein and D.K.Pearl (1979): Subjective Referral of the timing for a conscious sensory experience. Barain, 102, 1979, 193-224.

In the actual game coordinations occur to a split of a second between different parts of the body of the player as he adjusts to the movements of the other, without having time to think about it or plan it.

So, what kind of time is involved in a primordial dialogue during which the participants feel to be in communion with each other and exhibit postular echo and inter-coordination of gestures? In an intimate dialogue the participants are in each other's immediate present as participants of a self-enclosed dyad, not outsiders with movements mediated in observer's time. To the observer they are moving in time, or at least, time is being generated by the dialoging events. In what sense can they be said to share an immediate present? When they in rare moments exhibit perfect coordination and show by their bodily postures to be in attunement, in what way can they be said to share a "here-and-now"? When patterns of inter-bodily coordination and postular echo are exhibited, can they be taken as indications of interpersonal communion? If they are indications, can they be accounted for in terms of the language introduced in chapter 3? With such questions in mind I shall below refer to some philosophical ideas on time, and also venture an excursion into the domain of relativity. According to relativity two observers are precluded from sharing a "now" due to their different frames. But what about the different frames evoked by the single observer's bicameral sensory equipment or brain? Does this imply that even the individual is precluded a "now" in this domain?

If the participant observer is not precluded from being simultaneous with himself, then I shall venture the suggestion towards the end that there is a sense in which he may be seen to be partially simultaneous also with the other.

The present during protodialogue and affect attunement

For dialogue participants, even in the artificial surroundings of a laboratory, there may be a kind of relativity in socio-psychological terms of attention: For example, when observing (through one-way screen or though the camera eye) adults engaged in a dialogue, I have noticed how one of them may be seen to focus his attention solely on the other, while the other includes the camera in his attentional space, being aware also of the observer "out there". In such incidents, we might say that while the other and the observer are in the presence of one of the participants, the observer is excluded from the other's present and belongs to his past.

Similar incidents apply to events of protodialoging between an adult or elder sibling and a baby in home environments. Being aware of my camera recording the adult or elder sibling attend to the baby, while the baby is solely focussed on the other dialoging participant. While the baby and I are in the present of the adult and the sibling, only they are in the baby's present, while I may belong to the baby's future - until some camera noices or other things bring me and the camera into the baby's presence. The baby suddenly stops his engagement in the protodialogue and turns with apparent interest to the camera or camera-man. It may be elicited by a "false" note in the actual other, indicating that they may be momentarily out of attunement, or by noises made by the camera-man, or for some other reason. The parent or elder sibling will follow the baby's gaze and may even comment on it: "Ah, isn't grandpa funny?", or "You're more interested in grandpa and his camera (than in me)!?" The protodialoging has stopped. But the others may continue to be in the baby's presence. The baby may be attending the camera-man with his actual adult or elder other. That is, the actual other shares in the changed focus of attention. The baby turns with his actual other, who follows and accompanies his turning.

During what Stern describes as interpersonal communion or affect attunement between adult and infant, the baby may be engaged in some play, for example focusing on the doll, while the mother accompanies with comments the baby's doings. Only when a false note creeps in, or she turns her mind elsewhere will the baby turn to gaze at her, become an observer who reacts to the absence and dissolution of the affect attunement. There is a felt mutual presence and shared present in affect attunement, acknowledged only when it is broken.

The English term, "present" gives a clue for formulations of the problem of participants' present and observer's past.4 Actual participants are in each other's present in the multiple sense of this term: They are actually present to each other, they are in each other's present 'now', and what is more, each is offering himself or herself as a gift, as a present, to the other.5

Philosophy of the present (Peirce, Buber, Mead)

In his pragmaticism Charles Sanders Peirce was concerned with the tripartite ground for logic and comprehension, involving signs and relations between representations as necessary constituents. The sensory feeling quality is primary to mediation, and cannot be mediated as it is present. The feeling has passed before there is time to reflect upon it. We can never recapitulate that feeling in itself:

"..on the one hand, we never can think, "This is present to me", since, before we have time to make the reflection, the sensation is past, and, on the other hand, when once past, we can never bring back the quality of the feeling as it was in and for itself, or know what it was like in itself, or even discover the existence of this quality except by a corollary from our general theory of ourselves, and then not in its idiosyncracy, but only as something present. But, as something present, feelings are all alike and require no explanation, since they contain only what is universal. So that nothing which we can truly predict of feelings is left inexplicable, but only something which we cannot reflectively know. So we do not fall into the contradiction of making the Mediate immediable."(Peirce....)6

Peirce came to influence George Herbert Mead, who like Peirce considered thinking a dialogical process. A few months before his death Mead reads his Carus lectures at the meeting of the American Philosophical Association at Berkeley. Here he applies his principle of perspectives to the meta-physical domain of time and existence, which later came to be published in The Philosophy of the Present (1932). He deals with the social nature of the present as the locus of reality. To Mead the present is mediational, not immediate, mediating the generation of the future and the reconstruction of the past. Everything that exists, exists according to Mead in the present. Past and emergent future are in the present. The future emerging in the present involves the reconstruction of the past as part of this very same present. This occurs in the mental field. But the locus of the mind is not in the individual. The mental field is not bounded by the skin of the organism, but comprises the social through perspective-taking.7

Mead's way of posing questions about time and existence differs from the way in which such questions are pursued in phenomology and existential philosophy. Yet in many respects, his position may be compared to that of Martin Buber. In their different ways both give priority to dyadic and dialogical relations and stress the significance of time.

To Buber, the running arrow of time and mediational means-end relations belongs the sphere of I-It relations, not the I-You unit that emerges from an encounter in the immediate present. Neither the world nor the subject mediates the genesis or construal of a Thou. There is no monadic ego or self-enclosed I prior to or emerging from the primordial in-between encounter. He insists upon a primary distinction between the mode of being in an I-You unit, devoid of past and future, of means and ends, and being in an I-It relations, where other persons and things are made into objects and the arrow of time is flowing from past to future. Usually we are in the I-It mode, which is a mode of mediate relations which easily involve subordination and domination through means-end relations. In contrast, the I-You mode is immediate in the sense that the You is not construed or mediated by the I. The I-You unity emerges in the primordial dialogical encounter in the in-between of immediate reciprocity.

Neither past nor future, neither means nor ends, intervene between You and I in such a modality. That is why therapy, even in the Rogerian tradition of dialoging, will not admit an I-You union to emerge according to Buber.8 According to him the Thou meets an I in a relation that is direct, where "no system of ideas, no foreknowledge, and no fancy (keine Begrifflichkeit) intervene between I and Thou.9

In his studies of the social ontologies of Buber and others Michael Theunissen (1984:377) finds that the dialogic of Buber cannot "account for the origin of the I purely and simply out of the meeting with the Thou".10 Mead offers such an account in terms of the I and Me as aspects of the Self as a process arising through the infant's encounter with significant others. But this account brings Mead, unlike Buber's immediate I-You reciprocity, into a mediate present that involves the mediation of the generalized other. The child acquires the symbolic keys to such mediate intersubjectivity through playing and gaming with significant others. But how does the initial pre-understanding of the other in an immediate sense come about, required for this subsequent genesis of mediate understanding through the generalized other?

A reply to the above question was offered in chapter 3 supplementing Mead's view. The present thesis attributes to the newborn's mind an innate virtual other by virtue of which such an immediate pre-understanding of the actual other can come about. The self-organizing dyad of the infant's mind recreates itself as the infant's actual other replaces the infant's virtual other, and will again, when the infant-adult interplay is perturbed or comes to an end, reactivate itself in the infant's dialogue with the virtual other.

Can two self-organizing subjects be in coordinated attunement?

The account of protoconversation offered in chapter 3 entails a reply to a question that leibnizians of our times have to deal with (Cf. Maturana and Varela, 1980, 1981; Elster, 1990), namely, how two subjects or actors can engage in intersubjective relations of interaction.11 Leibniz monads were in attunement by virtue of God's pre-established harmony, or in modern versions, through the mediation of internalized language or norms of a common culture or cultural lifeworld. But such internalization of means for mediate understanding presupposes an initial immediate pre-understanding during the socializing events of interaction through which the means can be acquired in the first place. Accounts of how subjects can achieve intersubjectvity by virtue of shared acquired means of understanding call upon an account of how subjects in the first place is able at all to enter into immediate understanding.

While Descartes uses the predicate cogito to infer that the thinking subject exists as a monadic ego, Leibniz does the reverse. To Leibniz everything is contained in the monadic subject, not in the predicate.12 In his Discourse on Metaphysics Leibniz elaborates this conception. When several predicates are attributed to a single subject, and this subject is not an attribute of another, we speak of an individual substance. Even when the predicate is not explicitly contained in the subject, "it is still necessary that it be virtually contained in it." Leibniz mentions Alexander the Great as an example. While the quality of the king is not sufficiently determined to constitute an individual, "there was always in the soul of Alexander marks of all that had happened to him and evidences of all that would happen to him and traces even of everything which occurs in the universe" (VIII).

The universe is multiplied perspectively, according to each monad's viewpoint. Every individual substance expresses the whole universe in its own manner, each portraying the world in its own fashion, albeit in various degree of sharpness and confusion, all that happens - past, present, and future (IX).

Everything that happens to an "individual substance", or a "complete being" - past, present, and future - is already virtually included in its nature. Each monad has a certain self-sufficient autonomy, which makes them, "so to speak, incorporeal automata" (Monadology, 9, 18, 57). An individual substance cannot be made out of two, nor can it be divided in two. There is commencement, transformation, and perishing. A substance will come about only through creation, may undergo transformation, and will perish through annihilation (IX). Each individual substance, each monad, is the source of its own internal activity.13

In this way Leibniz, while denying the possibility of communication between monads, except through God's mediation, originates the idea of operational closure of cognition.

It was to be followed up by Kant in his consideration of the self-organizing nature of organic purpose,14"every part is thought as owing it presence to the agency of all the remaining parts, and also existing for the sake of others and of the whole......the part must be an organ producing the other parts - each, consequently, reciprocally producing the others...Only under these conditions and upon these terms can such a product be an organized and self-organized being, and, as such, be called a physical end."

I. Kant, The Critique of Judgement. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1980, Part II, paragraph 4 (65). Cited in: W. Krohn, G. Küppers, and H. Nowotny: Selforganization: Portrait of a Scientific Revolution, Kluwer, Dordrecht 1990, pp. 1-2. Uncovered by M. Heidelberger: 'Concepts of Self-organization in the 19th Century, in: Krohn et al., ibid, p.173.

In his study of concepts of self-organization in the 19th century, Heidelberg (1990) attributes to Kant, then, to be the first thinker to use the concept of self-organization in relation to systems of organic nature: Kant saw them as reproducing themselves from the inside, not caused from the outside. In this, as well as in his view upon the primacy of time, he is in debt to Leibniz, who, apart from the initial agency of God, denied any outside, causal influence on his perceptual monads; each was self-sufficient and closed, without any windows.

and by Piaget who describes mental structures in terms of auto-regulation and finds that intelligence organizes itself by organizing its world.

Operational closure entails that no formative or in-formative organizational elements that are involved in the self-recreation of the system comes from the outside of the system. It is able to recreate itself and maintain stability through the recursive operations of its own elements constituting the system and its boundary - even when transforming itself from less to more complex states of organization.15

This means that an operationally closed system is closed with regard to its self-reproducing mechanisms that maintain its organization,16 or, as Piaget would say, its structure. For example, Piaget describes mentality structures to be self-regulative in this double sense: First, their compositions do not go outside their own boundaries. Second, they do not make any appeal to anything outside the boundaries. In other respect they are open, interwoven as they are in ecological, biological, social, and personal life processes. Outside causal agents may even play the role of perturbing or destroying the system. If they play, however, a formative role in the maintenance of some system, this system would per definition not be a self-organizing system.17 That is why Piaget, for example, insists upon the process of assimilation. Only when outside elements are transformed into system-internal elements through the process of assimilation, can they play a part in the auto-regulation of the system.

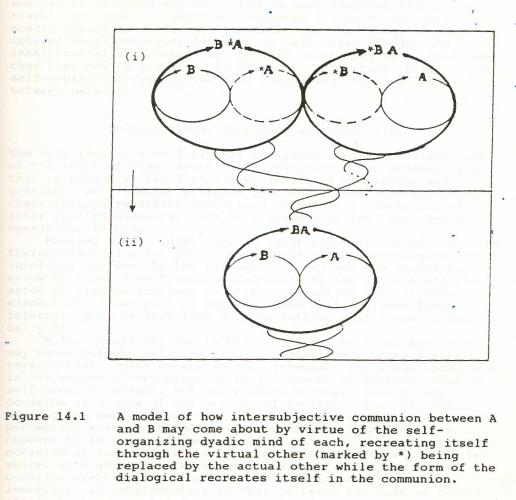

In such terms Piaget could state that intelligence organizes itself by organizing its world.18 The thesis brought forth in this book invites this addition: through dialoging with the other, actual or virtual. The self-organizing dyad of the mind recreates itself accross the domains of intra- and interpersonal immediate understanding, complementary to domains of mediate understanding. This entails an alternative to way in which Leibniz accounted for intersubjective harmony. Harmony, and conflict for that matter in reciprocal loving or hating relationships, has been specified above to come about by virtue of the participants qua actual others replacing each other's virtual other in a mode of felt immediacy (Cf. Fig. 14.1).

The above diagram indicates how two autonomous systems, conceived in terms of their primary dyadic constitution, can combine to form a unity without any change of their identifying dialogic closure. The double helix-like figure indicates how the virtual other of each of them is being replaced by each other qua actual other. This is implied to occurr without any intervention or mediation. The upper part indicates the innate dialogic organization involving the complementary participation of the virtual other, marked by a star. The actual other fills the inner companion space (marked by the star (*)) in a reciprocal mode of felt immediacy, as illustrated by the the lower part (ii) of the diagram, while the primary form of the dialogical maintains itself. This permits this qualitative prediction: If intra-personal synchrony occurs and can be measured and described in some adequate frame, for example in terms of concurrent neuronal firing or activation of muscle groups at different locations, then one should expect interpersonal synchrony to occur as well. Even though such interpersonal occurrences may be rare, were they to be confirmed, then they invite an account in terms of the present thesis. It is relevant to domains of intra-and inter-bodily attunment and "postular echo" to be turned to towards the end of this chapter.

The thesis of the virtual other, then, permits the combination of the two basic ideas considered above pertaining to the nature of the mind. The first is the idea of the dialogic nature of man introduced by Feuerbach, and developed Buber, and, independently, by Peirce and Mead as recounted above. The second idea is that of the operationally closed nature of cognition, which may be recognized in cybernetic ideas of self-organizing systems, for example in the biological principle of autopoiesis introduced by Humberto Maturana.19 The first to advance in precise terms the idea of closure in cognition and conversation were Heinz von Foerster20 and Gordon Pask,21 followed by Francisco Varela.22 Seen to be pertaining to different domains, ideas on dialogue and self-organization of cognition have otherwise until now largely been entertained in separate avenues of thought (See, however, Edgar Morin, 1981)23.

Presentational immediacy and relativity

The very idea of a self-organizing system invites the issue of time. Spontaneous emergence of an organization that re-produces itself at higher levels of complexity and generates self-similar patterns of order amidst apparent noise or chaos through recursive operations of a fairly simple set of inter-related elements, entails a dynamic system, and, hence, operations in time.

Hawking (1988) identifies at least three arrows of time: the thermodynamical arrow involving disorder; the psychological arrow involving our feeling the passage of time; and the cosmological arrow of time. Ilya Prigogine demonstrates how an irreversible arrow of time is involved in self-organization even at the elementary micro-level of physics, when distinguished from internal ages, be they from past or future, that appear symmetrically.24

While relativity denies that there can be simultaneouty in any sense but the relative one, Whitehead comes forward with a version that admits presentational immediacy for actual occasions in the unison of becoming. He is influenced by Leibniz' idea of self-creative monads, but not without windows. Each actual occasion is a mode of the process of feeling the world, "of housing the world in one unit of complex feeling". There can be perception even in the mode of presentational immediacy, as opposed to re-presentational mediacy. Whitehead regards an actual occasion as includes in its own immediate present, which can be shared with another in a unison of becoming. Thus, an actual occasion prehends other actual occasions in presentational immediacy, as complementary to what he terms the mode of causal efficacy. Being included in its own immediate present each actual occasion defines one duration in which it is included. But an actual occasion, A, may lie in many durations, where each duration including A also includes some portion of A's presented duration. In relation to a percipient actual occasion, A, then, there are actual occasions in A's causal past, as well as actual occasions that are A's contemporaries, perceived by A in the mode of presentational immediacy. Thus, for example, B and C may both be contemporaries of A, immediately perceived by A, while B and C are not contemporaries of each other. That is, A and B lie in the same duration, and A and C lies in the same duration, sharing in Whitehead's terms, a unison of becoming, while B and C are not in a unison of becoming. This makes A and B contemporaries, and A and C contemporaries, while B and C are not contemporaries of each other.

Relativity's denial of simultaneity

In this way Whitehead offers his special interpretation of relativity, while opening also for a "directly perceived immediate present". This Einstein could not accept. He conceded that many problems would be solved if it were true, but that it would make non-sense of any two observers speaking about the same event.25

"...When Whitehead affirms an intuitively given meaning for the simultaneity of spatially separated events, he means immediately sensed phenomenological events, not postulated physically defined events. ...We certainly do see a flash in the distant visual space of the sky now, while we hear an explosion besides us. His reason for maintaining that this is the only kind of simultaneity which is given arises from his desire...to have only one continuum of intuitively given events, and to avoid the bifurcation between these phenomenal events and the postulated physically defined public events."

Einstein exclaimed that so many problems would be solved if that were true, but that, unfortunately, it is a fairy tale. He adds: "On that theory there would be no meaning to two observers speaking about the same event." (Schillp, p.204) Whitehead might have agreed to that claim. When speaking about some event, the observers would no longer in the mode of presentational immediacy. But, as I shall indicate below in terms of the thesis of the virtual other, qua participants in the companion space of each other, lying in the same duration, they might share in "the same event", for example an event of discovery, in a unison of becoming.

Einstein denies any shared immediate present for two observers, A and B. He proposed that the concept of absolute simultaneity be dropped, and replaced by relative simultaneity, that is, relative to the frames of reference of each observer. This means that what may lie in A's past, may very well, dependent upon the frame, lie in B's future. In the domain of relativity two observers, A and B, cannot share an absolute "now" and be truly simultaneous.

If the domain of relativity were to apply to the thesis brought forth in this book this curious consequence would follow. An observer could not even be simultaneous with himself. The perspectives attributed to the observer's self and virtual other are complementary, and hence, involve different frames of reference. So, it appears that what we may have gained in explanatory power with respect to phenomena accounted for in this book may have to be balanced against the cost of creating paradoxes with respect to time. For, surely, the individual person would have to be considered to be simultaneous with himself, or, would he?

Even though the domain of relativity does not coincide with the domains considered in this book let me venture some conjectures on the kind of inferences that might be drawn from the thesis if it were to apply to observers qua participants in an event of discovery. If we maintain for the time being, as relativity does, that an observer at least can be said to be simultaneous to himself, then there is a way in which two observers can be seen to be partially simultaneous with each other.

According to relativity there can be no shared 'now' for two observers, A and B. The closest we can get to such a concept, Roger Penrose points out, is in terms of the observer's 'simultaneous space' in space-time, depending on the motion of the observer. But even for two observers, A and B, slowly crossing each other's paths there would be differences in the time-ordering for events at a distance. Penrose (1989:201;303) illustrates this in the following manner: Imagine two people A and B walking slowly past each other. An event at a distant galaxy of launching a fleet to wipe out earth, judged by the two people to be simultaneous with the moment they pass one another may actually lie in the past of A, and in the uncertain future of B. For A the fleet may already be under way. For B, the fleet has not yet got off the ground and may never do.

Thus, the 'now' to one of the observers would not agree with the 'now' of the other and what lies in their respective past and future may differ. An event, E, may be in A's past, while E lies yet in the B's uncertain future.

This entailment of modern physical theory rests on the assumption, however, that an observer's 'simultaneous space' in space-time is attributed to the observer considered as a singular monadic entity, entertaining one observational view.

Simultaneity in terms of the virtual other

What if the observer were to be regarded as a dyadic entity, housing two complementary observational perspectives, a self and a virtual other. If one attributes such a dyadic organization to the observer, then there may other possibilities for considering simultaneity. Qua participants in the immediate present of each other's companion space, replacing each other's virtual other, they might share "the same event", for example that of partaking in an event of discovery, in a unison of becoming.

Imagine first this situation. A nuclear scientist, called Ann, has designed a collision experiment in the hope of detecting tracks of a new kind of particle predicted by their model. If the new kind of particles are detected as a result of the collision a particular form of tracks will appear on the screen on the basis of the input from the particle detector. Eagerly and expectant awaiting before the terminal of the computer that processes the detector input, Ann instantly recognize the new track form the moment it appears on the screen. What about Ann is it that partake in this moment of discovery? Is it the whole of Ann's consciousness as the separate firings in her sensory organs and brains combines to evoke awareness of the track produced on the screen. What about the excitement that she feels at the moment, perhaps even elicited moments before her reflective awareness comes into operation? Let the presentational immediacy of Ann be described in terms of the union of becoming of Ann's self A and Ann's virtual other *B. In these terms it makes sense to state that Ann's exciting moment of discovery extends to include the participation of Ann's self and virtual other in a union of becoming.

Now, imagine instead this modified situation in which Ann has been building the model and preparing the experiment in close rapport and collaboration with her colleage. Bill. They are sitting before the screen waiting to see if the track form, as predicted and specified by their model, will occur on the screen. The "moment" it appears on the screen Ann and Bill instantly recognize in each other's presence the new track form. In what sense can they be said to share in each other's moment of discovery?

In the previous thought experiment, when Ann was alone, she was permitted to be considered to be simultaneous with herself in terms of the presentational immediacy of Ann's self A and Ann's virtual other *B in a union of becoming. Let Bill by himself be described in similar terms. That is, let the presentational immediacy of Bill be described in terms of the union of Bill's self B and Bill's virtual other *A. If each of them can be said to be in presentational immediacy with herself or himself, that is, in union with the virtual other, then there may also be a partially shared presentational immediacy for Ann and Bill when each qua actual other replaces the other's virtual other at the shared moment of discovery. By virtue of Ann's union (A,*B) with herself she can enter in (comm)union (A,B) with Bill through replacing Bill's virtual other, *A. In line with the notation previously introduced. this may be succinctly indicated as follows:

Before the discovery: At the shared moment of discovery: Ann's union: A,*B := A,B i.e. Ann and Bill in (comm)union Bill's union: B,*A Above the sign ":=" stands for "becoming." By virtue of the primordial dyadic constitution they can be joined in a union of becoming at the moment of discovery. As long as we concedes that Ann in the previous thought experiment could be simultenous with herself, that is that Ann's A and *B are simultaneous (cf. Fig. 14.1 (i)), then, in the modified situation, when Bill replaces Ann's virtual other *B, then Ann and Bill can be said to be partially simultaneous (Cf. fig. 14.1 (ii)).

If we lift this requirement, then there can be relativity even accross each person. For example, that which would lie in the uncertain future for A (of Ann) replacing Bill's virtual other, *A, may lie in the past of B (of Bill) replacing Ann's virtual other. But this entails, then, the paradox that each participant observer is relative even to herself or himself, that is, to the complementary perspective or frame of his virtual other.

Interpersonal bodily attunement and postural echo

When engaged in the kind of rapport or communion that involves the immediate presence and participation of the actual other, their rapport will sometimes be appearent by the way in which their bodies and facial expressions exhibit matching forms of posture and gestures that resemble or complete each other.

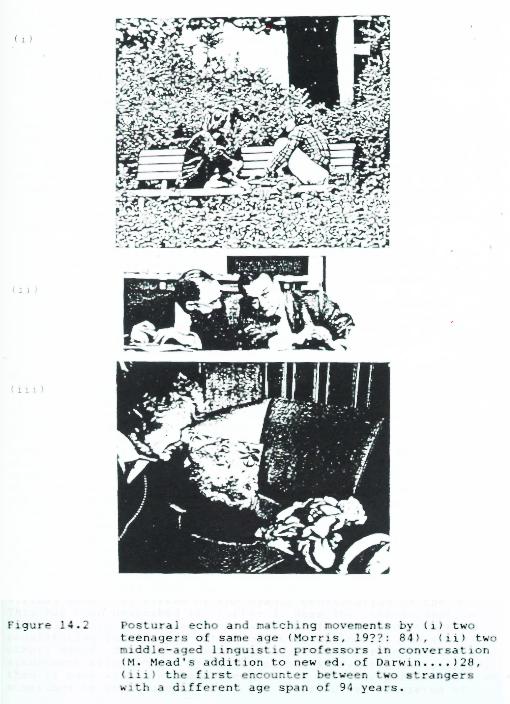

Regard the three snapshots shown in Figure 14.2. The first show two teenagers of the same age in dialogue. Both their facial expressions and bodily postures are beautifully matched, indicating that they are close to each other in spite of the physical distance. The second shows two speakers on linguistics at conference on culture and communication. Notice they way in which their hands lift in the same manner from the table as one of them is talking and the other listening. The third snapshot shows the first encounter between two strangers, with 94 years of age difference. At first they only tentatively and with probing caution approached each other before each greets the other with matching smiles and facial expressions.

Encounters between strangers will often generate quite a different pattern from the snapshots in (i) and (ii). If as we say, their bodily "chemistry" is out of tune with each other, their disparate body movements and different gesticulations, will strengthen the feeling in the other of facing a stranger. The same applies to conversation between people who are stressed, disturbed, exhibiting divided attention, depressed or mentally perturbed. For example, In their sound-film analysis of normal and pathological behavior Condon and Ogston (1966) find that in recorded observations with some mentally disturbed patients there occurred little or no interbodily coordination. (Cf. also studies by Murray of infant-mother interplay when the mother is depressed, referred to in chapter 4).

The autistic person will exhibit self-enclosed movements that expresses the exclusion of the actual other. Autistic twins, however, have been reported to manifest movements and gestures indicative of communion. Oliver Sacks (1986:186) tells about his meeting with the twins, John and Michael, when they were 26 years old. They exhibited, when together, not when they became separated, this remarkable capacity to say at once on what day of the week a date falls far into the past or the future. At first encounter they appear as a sort of "Tweedledum and Tweedledee, indistinguishable, mirror images, identical in face, in body movements.."26 When telling, say, the date of Easter in the last or next forty thousand years, their eyes move and fix in a peculiar manner - "as if they were unrolling, or scrutizing, an inner landscape".27 Sachs records how he watched their seated in a corner together, with a secret, mysterious smile on their faces, engaged in an exchange of six-figured prime numbers, "and which they 'contemplated', savoured, shared, in communion."28 "Deprived of their numerical 'communion' with each other...they seemed to have lost their strange numerical power, and with this the chief joy and sense of their lives." Sachs,....,199

When looking at an unperturbed person gesticulating and talking through a table phone, one may sometimes notice matching movements between the left and right side of the body. But thee may also occur mismatching movements, for example, with right eyebrow and right hand raised, while left hand may be leaning downward. If the person is stressed, or disturbed, or out of tune with himself, jerky and seemingly uncoordinated movements pointing in different directions may be seen.

The unperturbed talker's movements in a face-to-face relation are different. Unless they are arguing, with the talker leaning forward and the listener leaning backwards in a skeptical posture, they may come to exhibit matching movements and postures that indicate inter-bodily attunement. When the other echoes one's bodily posture and movements feelings of warmth and attunement may arise. When there is mutual attunement or strong rapport even tiny movements, the stretching of the lips, the raising of a finger or a hand, may come to be matched by the other in a way that indicates interpersonal bodily attunement. Desmond Morris terms this "postural echo":

"When film shot at 48 frames per second is analyzed frame by frame, it is possible to see the ways in which sudden, small movements start simultaneously, on exactly the same frame of film, with both the speaker and the listener. As the speaker jerks his body with the emphasis he makes on different words, so the listener makes tiny, matching movements of some part of the body. The more friendly the two people are, the more their rhythm locks together."(Morris,19.., p.85)30

(Cf. also A. Kendon, 1970)31A. Kendon: Movement coordination in social interaction, Acta Psychologica, 32, pp. 110-125;

A.E. Scheflen: Body Language and the Social Order, Englewood Cliffs, Prentice Hall 1972;

Desmond Morris..........referring to the above.

Similar features sometimes emerge from analyzes of video-tape recordings of infant-adult protoconversation, and of adult friends in intimate conversation. A fine bodily attunement is revealed. They show themselves to enter into similar bodily postures and gestures, sometimes in perfect co-ordination, as if they were of one body, not two. For example, Fig.2.1 (in chapter 2) showing snapshots of a baby at the nursing table in interplay with her mother indicate clear signs of reciprocal gestural and attunement. The gestures and bodily postures of each may be seen to reflect a degree of intimacy. There is reciprocal co-ordination of small body movements.

Such postural echo and inter-bodily attunement can be accounted for in terms of the thesis of the virtual other inviting replacement by the actual other. Interpersonal communion with the actual other may be seen to come about when the actual other replaces the virtual other, by virtue of the dyadic constitution of the mind. This was specified in chapter 3. Here the intersubjective communion with the actual other was specified to have the same constituting form as the intrasubjective union with the virtual other. Hence, if it makes sense to say that a person can be in attunement with himself by virtue of his intrapersonal feelings, then it make sense in these terms to say that the person can also sometimes be in attunement with the actual other by virtue of interpersonal feelings in the same format (Cf. fig. 14.1). Intrasubjective feelings are evoked in the intra-personal domain of B's union with his virtual other, *A; intersubjective feelings are evoked in the inter-personal domain of B's communion with his actual other, A.

Conclusion: the distinguised companion

This may also apply in a modified format to religious phenomena of dialogue and communion. They invite an account in the format of transitional phenomena, specified in chapter 4.

Here was indicated how the baby by virtue of its self-creative dialogic organization is able to transform some "object" (as seen by the adult observer) into an actualized other in the companion space of the baby's virtual other and engage in communion with this "transitional object", as Winnicott terms it. This act of creation will enable the infant, when left alone, in need of comfort, or going to sleep, to re-enact dyadic togetherness with a actualized companion by virtue of the dyadic organization of the infant's mind. In subsequent chapters I have returned to the way in which children's play with invisible companions and preschooler's and adult's self-conversational engagement in some object or subject matter can be considered in the same format. That is, this actualized other becomes a participant in the person's dialoging or communion. The companion space of the person's virtual other is filled by the object or subject matter in a way that actualizes it as a dialogue companion, endowed with life in interplay.

If the above applies to religious phenomena one can understand how thinkers on religious experience, like Bachtin,32 Buber, Feuerbach, and McMurray33, in their different manners and traditions have come to emphasize the inherent dialogic nature of man. While the rationalistic philosophers established the monadic ego as the thinking I in abstract reason, Feuerbach proposed, in his Principles of the Philosophy of the Future, that the nature of the essence of the human being is dialogical and grounded in feeling:

"Whereas the old philosophy said: that which is not thought of does not exist, so does the new philosophy say in contradistinction: that which is not loved, which cannot be loved does not exist." (35)

Here Feuerbach turns against the abstract dialects of Hegel with his focus upon ideation and mediation. In contrast, Feuerbach insists upon the immediacy of the senses, of perception, of feeling. Whereas the old philosophy begins by saying: "I am an abstract and merely a thinking being to whose essence the body does not belong" (36), Feuerbach considered the body in its totality to belong to the essence of I as a sensuous being. To be is furthermore to be in fulfilled time, while time in the imagination is empty time. Time and space are conditions of being. To be here is the primary being. My index finger pointing to me, or you, is the signpost from nothingness to existence (44), but not in isolation:

"The essence of human being is contained only in the community and unity of man with man (in der Einheit des Menschen mit dem Menschen) - a unity, however, which rests only on the reality of the I-You distinction (die Realität des Unterschiede von Ich und Du)."(59) (Feuerbach 1843)34

We find similar statements in the work of Buber, in the early work of Bachtin, and in MacMurray's thought on religious experience. They all point, in their different ways, to the inherent dialogicity of human beings. Above I have pointed to the way in which their basic insights may be linked with the notion of the self-organizing dyadic mind, and with Winncott's notion of transitional objects. That is, the self-organizing mind may be seen recreate itself in dialogue with the other, actual or virtual, and allow for lived moments of communion with Nature, with God, or with man-made creations such as Mozart's music, actualized as an Other in the companion space of the virtual other.

Feuerbach's distinction is considered by some to be a Copernican revolution of modern thought,35 perhaps as rich in its potential consequences for the sciences of mind and society as the effect on atomic physics of Paul Dirac's finding of the companion particle to the electron. When formulating and solving in quantum theoretical terms the equation that describes the electron, Dirac found his equation to have additional solutions that entailed the existence of a companion particle to the electron, with the same mass, but with opposite charge. When the quantum creation of the particle pair of electron and positron was experimentally confirmed, the simple conception of elementary particles existing in themselves in the image of Democritus' atomic unit had to be discarded. The way physicists thought about the nature of matter was radically changed.

The way we think about the nature of mind cannot be expected to change in such a radical and abrupt fashion. In the sciences of mind and society there is no basic equation to be solved and no decisive experiment to be performed that could radically change the outlook overnight. And yet, if that had been the case, I believe one would find no natural unperturbed mind in operation without the concurrent participation of a companion, actual or virtual. At least, such is the credo concerning the nature of mind presented in this book. By virtue of the operationally closed communion with the person's Virtual Other, the person is open to lived moments of communion with actual and actualized Others.

E161191 NOTES TO CHAPTER 14

1The phenomenological distinction between participant and observer, made by the Norwegian philosopher Hans Skjervheim, is helpful for distinguishing participants' present from the time and position of the observer. Cf. Hans Skjervheim: Objectivism and the Study of Man, Inquiry, vol. 17, Nos. 2 and 3, 1974. See also H. Skjervheim: Vitskapen om mennesket og den filosofiske refleksjon, Oslo, Tanum 1964.

2R. Penrose (1991): The Emperor's New Mind: Concerning computers, minds, and the laws of physics. Oxford University Press, New York, Vintage ed. 1991 pp.568-573.

E. Harth (1982): Windows of the Mind. Harvester Press, Hassocks, Sussex 1982.

3L. Deeke, B. Grötzinger, and H.H. Kornhuber (1976): Voluntary finger movements in man: cerebral potentials and theory. Biol. Cybernetics, 1976, 23, 99.

4Cf. Hans Skjervheim's distinction between the participant and the observer in "Science and the Objectivity of Man"???? Inquiry,.....

5Cf. The Concise Oxford Dictionary, 1964:963):

6C. S. Peirce: Some Consequences of four Incapacities. Journal of Speculative Philosophy, vol.2, 1868. In: Collected Papers of, The Belknap Press, Harvard 1960, p.5.289.

7Half a century later Gregory Bateson, in his Steps to an Ecology of Mind, was to make almost a similar statement about the mind that is not bounded by the skin, but extends to encompass a closed circuit that goes beyond the body...

8Buber's position entails that there be transitions between I-It and I-Thou states, that these two kinds of states cannot occur in parallel. This presupposition may be questioned. While it is possible to describe cases of mediate relations in which there is empathologic collapse and pure means-end considerations of the other, some kind of immediate intersubjectivity, involving positive or negative feelings, may be underlying even mediate distant relations in which the other is made an object.

9This makes his approach different from Mead's symbolic interactionism which assumes self-reflective representation and mental simulation as prerequisites for understanding (Cf. Bråten, 1973 a,b).......

10Michael Theunissen: The Other. The MIT Press, Cambridge 1984, p. 377.

11To leibnizians of our time the phenomenological question of how two subjects, when one of them is a stranger to the lifeworld of the other, can engage in intersubjective interaction, has posed a problem. Cf. for example, Maturana and Varela, 1980; H. Maturana and F. Varela (1980): Autopoiesis and Cognition, 1980... See also their discussion and different positions on interaction in Zeleny (ed.)......1981. Cf. also Elster, 1990 from quite another perspective J. Elster: Cement of Society, Cambridge University Press, 1990...). In self-organizing systems terms, the question turns almost paradoxical: How can two operationally closed monadic individuals, A and B, partake in a self-organizing dyad, AB, without loss of their respective identifying organization? The solution entailed by the account in the previous chapters and elsewhere is this: If each already has a dyadic organization, involving the participation of a virtual other, then this dyadic organization may recreate itself when each, as an actual other, replaces the virtual other (Bråten, 1988 a,b).

12"In consulting the notion of I have of every true proposition, I find that every predicate, necessary or contingent, past, present, or future, is comprised in the notion of the subject, and I ask no more........for it follows that every soul is a world apart, independent of everything else except God.." (Leibniz in Russell (1961:573); Sherover (1975:135)).

13"One can learn the beauty of the universe in each soul if one could unravel all that is rolled up in it, but that develops perceptively only with time." (Sherover,...584,note 149).

14In his account for purposiveness in the Critique of Judgment Kant gives a description of self-organizing processes in organic terms (Cf. Krohn et al., 1990, pp.1-2, 173): In contrast to an instrument of art, in natural product,

15To regard a system as closed with regard to its identifying self-organizing operations does not entail that outside sources of energy or other substantial resources are not made use of. But such outside sources and resources from the outside do not play a formative and organizational role. Chaos theory offer instances of self-organizing systems in several domains where natural resources are made use of, for example, cloud formations, liquid patterns. This is even partially reflected in the mathematical models used to generate chaos-theoretical patterns. The recursive loops that operate upon their own products in generating self-similar and self-replicative patterns, are closed with respect to their recursive operations, but open with respect to the energy-matter (and initial values) provided by the environment.

16The domain of vision, referred to in chapter 13, provides other examples of how self-organizing systems may be closed with respect to operations, and yet open with respect to light stimuli from the environment.Singer (1990), in his search for a basic principle of cortical self-organization in vision, indicates how selectively coupled feature detectors may self-organize and exhibit synchronizations across spatially separate columns if elicited by stimuli showing coherent features. W. Singer: Search for coherence: A basic principle of cortical self-organization. Concepts of Neuroscience, Vol. I, No. 1 (1990), 1-26. Studies of frogs' pigeon's vision were also the basis for Humberto Maturana's coining the term "autopoiesis" and developing with Fransisco Varela principles of biological autonomy. See Zeleny....., Varela.....

17Thus, the neurocomputional models considered in chapter 13 cannot strictly said to self-organize, even when implemented from a self-organizing systems perspective, since the designer plays a formative role, even though less formative than for knowledge-based systems.

18This is the point of departure for radical constructivism, developed by Ernst von Glasersfeld, who nevertheless recognize the existence of the other, albeit only as be construed....

19A study of frog's vision, with Letvin and McCulloch, was actually the generic experiment that set Maturana on the path of developing with Varela the principles of autopoiesis. The point of autopoiesis (auto = self; poiesis = creation, production) is the operational closure whereby the system, with its constitutive interacting elements, creates itself and re-creates its identifying organization without access to any formational elements outside the boundary. For example, when a biological cell is regarded as operationally closed in its self-production in terms of autopoiesis, this does not entail that it is closed in other respects. It is coupled to other cells for various kinds of exchange through what Maturana and Varela term structural coupling.

20Ref to papers by Foerster...

21Ref to papers by Gordon Pask.....

22F. Varela (1981?): Principles of Biological Autonomy, North Holland.......

23E. Morin:....in Zeleny......See also....

24Ilya Prigogine: Order out of Chaos, Bantam Books, 1984, p.289.

25Not long before Einstein died, he raised the point in a discussion with the philosopher Northrop, who replied in this way:

26Oliver Sachs: The man who mistook his wife for a hat. Picador, Pan books 1986, p.186.

27ibid, p. 187.

28ibid. p.192. In 1977 the twins were separated through an act of intervention with the explicit purpose to prevent their 'unhealthy communication'and enabling them to face the world in a socially acceptable way. Sachs points out:

29M. Mead's addition of photo illustrations to Darwin.......The phote by Simpson Kalisher of speakers at the Lousville University Institute on Culture and Communication, ....p.iv, plate VI.

30Desmond Morris:..........W.S. Condon and W.D. Ogston: Sound Film Analysis of Normal and Pathological Behavior Patterns, Journal of Mental and nervous Disorders, 143, p.338-347.

31F. Davis: Inside Intuition. McCraw Hill, New York 1971;

32References to Bachtin, especially from the 1920's...

33J. MacMurray: Persons in relations. London: Faber and Faber Lit., 1961. See also ....The structure of religious experience....

34Ludwig Feuerbach: Grundsätze der Philosophie der Zukunft (1843) Klostermann, Frankfurt a.M. 1983, pp.90-91; 110 (Cf. transl. by M. Vogel, Hackett Publ. Co. 1986, pp.54; 71)

35Cf. M. Buber: Between Man and Man, Macmillan, New York 1965, p.148.

TO SEE THE INDEX OF TEXTS IN THIS SITE, CLICK HERE